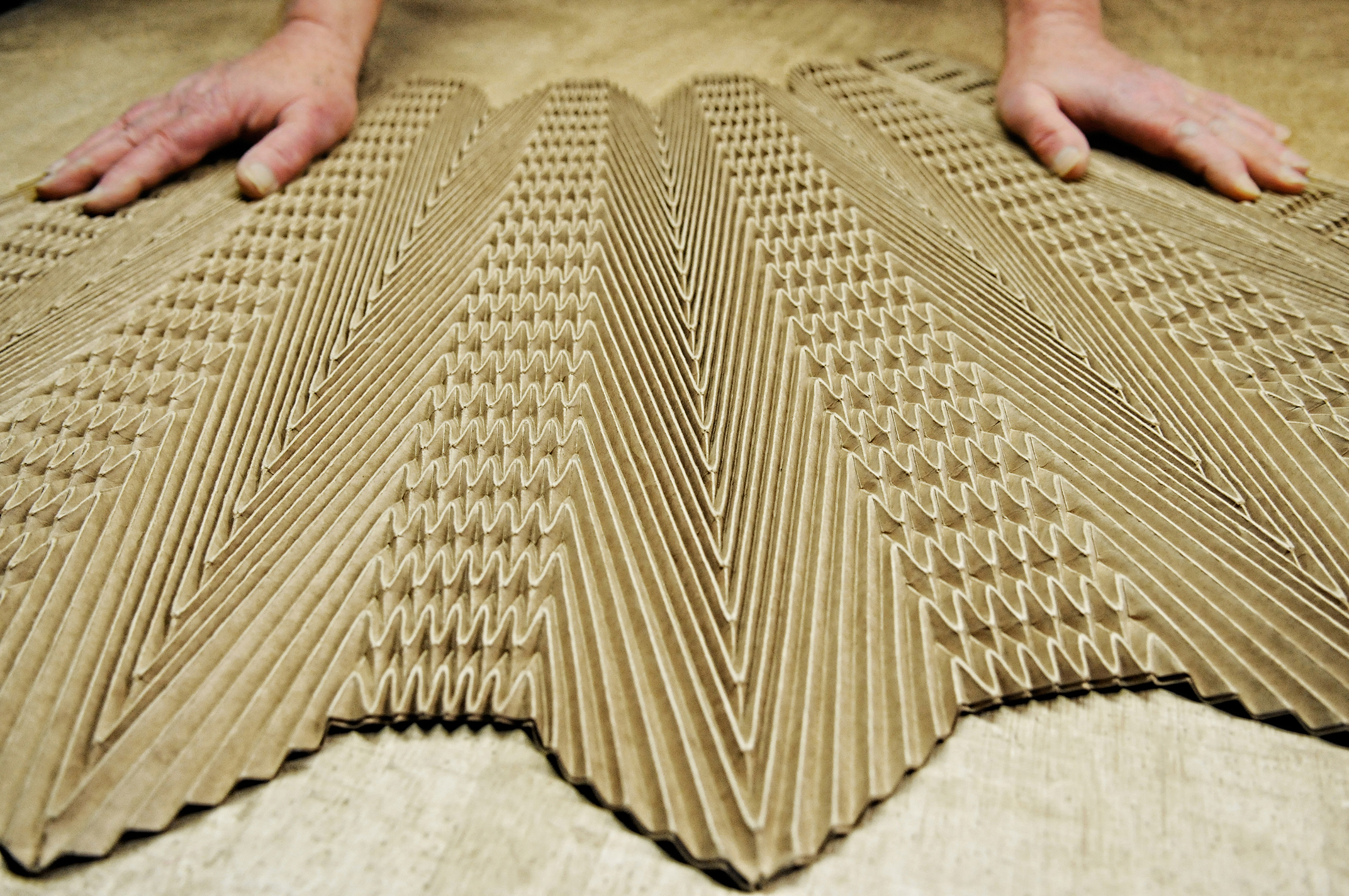

Detail of a pleated dress for Armine Ohanyan.

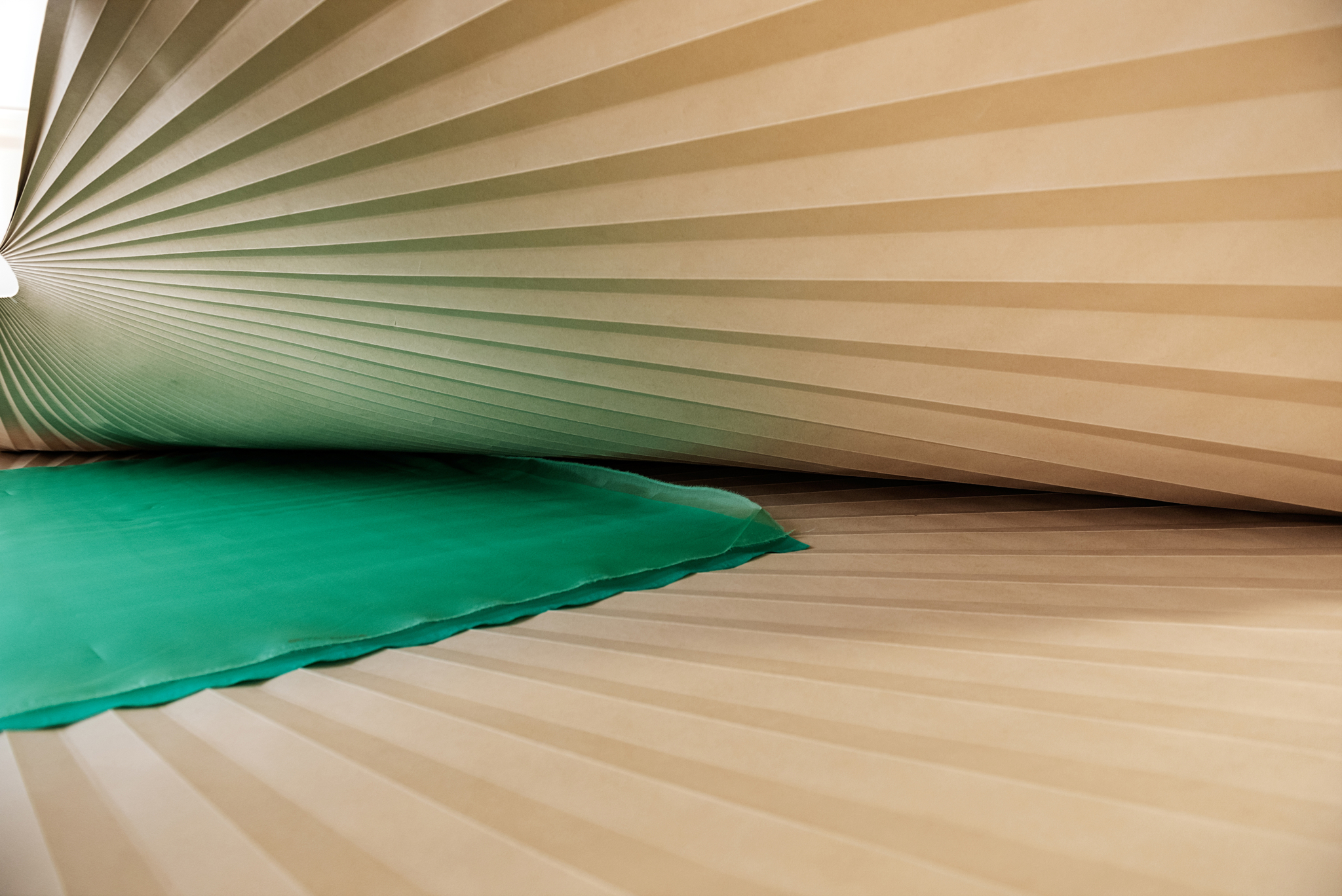

Karen Grigorian with sunburst pleating pattern wide open.

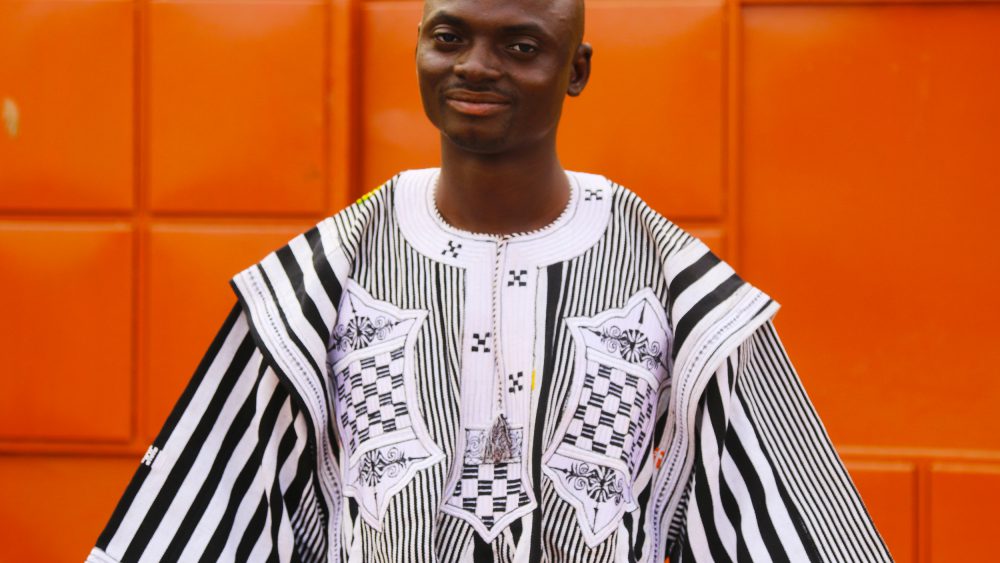

Karen Grigorian is the spiritual successor to pleating-master Gérard Lognon, who was his boss and mentor for 14 years. Karen now runs his own studio, Maison du Pli, where he can pursue his craft and utilize his full talent. Hints of his 25 years of practice are visible in every corner of the studio, a spacious venue clearly arranged to optimize every step of the labor-intensive table pleating process. A collection of 300 exclusive patterns are rolled up and stacked in the basement next to a custom-built steam cabinet. Whether it is silk, organza, wool, cotton, velvet, leather or woven bronze threads, the studio welcomes the challenge of working with a variety of fabrics. The proud keeper of rare artisan skills, Karen works with prestigious haute couture houses such as Givenchy, Fendi, Hermès, Céline, Valentino, Margiela and newcomer Armine Ohanyan Paris.

“I’m totally passionate about my craft because I enjoy working with my hands. It gives me great satisfaction, especially when I create a new pattern or mold. This passion is my driving force,” Karen explains. “It takes dedication, and maybe a little faith, to pursue this craft when there are less than 10 pleat workshops left in France. In its heydays, the famous Lognon Atelier had 70 employees, but only 4 to 5 employees in the 2010s. Maison du Pli is the only independent pleat workshop remaining in Paris.

(Left) Pleating mold. (Right) Silk chiffon in sunburst pleat right before being removed.

To enjoy the full story, become a Member.

Already a Member? Log in.

For $50/year,

+ Enjoy full-length members-only stories

+ Unlock all rare stories from the “Moowon Collection”

+ Support our cause in bringing meaningful purpose-driven stories

+ Contribute to those in need (part of your membership fee goes to charities)

Maison du Pli was established in Paris’ Belleville neighborhood by pleating-master Karen Grigorian. Born in Armenia in a chess family with a passion for Russian and French literature, Karen entered the textile and fashion industry when he moved to Paris in 1990. Benefiting from the skills and experience of its founder, Maison du Pli is entirely dedicated to table pleating. Karen creates all the paper molds he uses to pleat fabrics, leather and other various materials. He makes orders for fashion couture houses, theatres and design studios.

Anne Laure Camilleri is a freelance photographer based in Paris. She studied Film Making at the Conservatoire Libre du Cinéma Français and worked as a post-production supervisor before shifting to photography. Combining her passion for arts, journalism and cultural preservation into her features, she explores the spiritual values that permeate traditional craftsmanship and maintain cultural resilience. Her features have appeared in various media outlets including Selvedge, Embroidery, Inspirations, Handwoven and Pèlerin.

EDITING: COPYRIGHT © MOOWON MAGAZINE /MONA KIM PROJECTS LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

PHOTOS & TEXT: COPYRIGHT © ANNE LAURE CAMILLERI. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TO ACQUIRE USAGE RIGHTS, PLEASE CONTACT US at HELLO@MOOWON.COM