An old brick chimney

rises above the rooftops of the historic building where the iconic Faribault wool blankets have been traditionally crafted for over 150 years. Wool processing has not changed much since the early days of the mill. Modern equipment runs faster but the raw material, the natural fiber, the wool, still comes from four-legged creatures that cannot be rushed. Compelling facts from the Mill reveal that “one sheep gives 7,5 pounds of wool per year, one carding machine processes 400 pounds in a day, that are later spun into 60 cones of yarn. Overall, it takes one year for 3 sheep to grow the wool to make 2 military twin size blankets.”

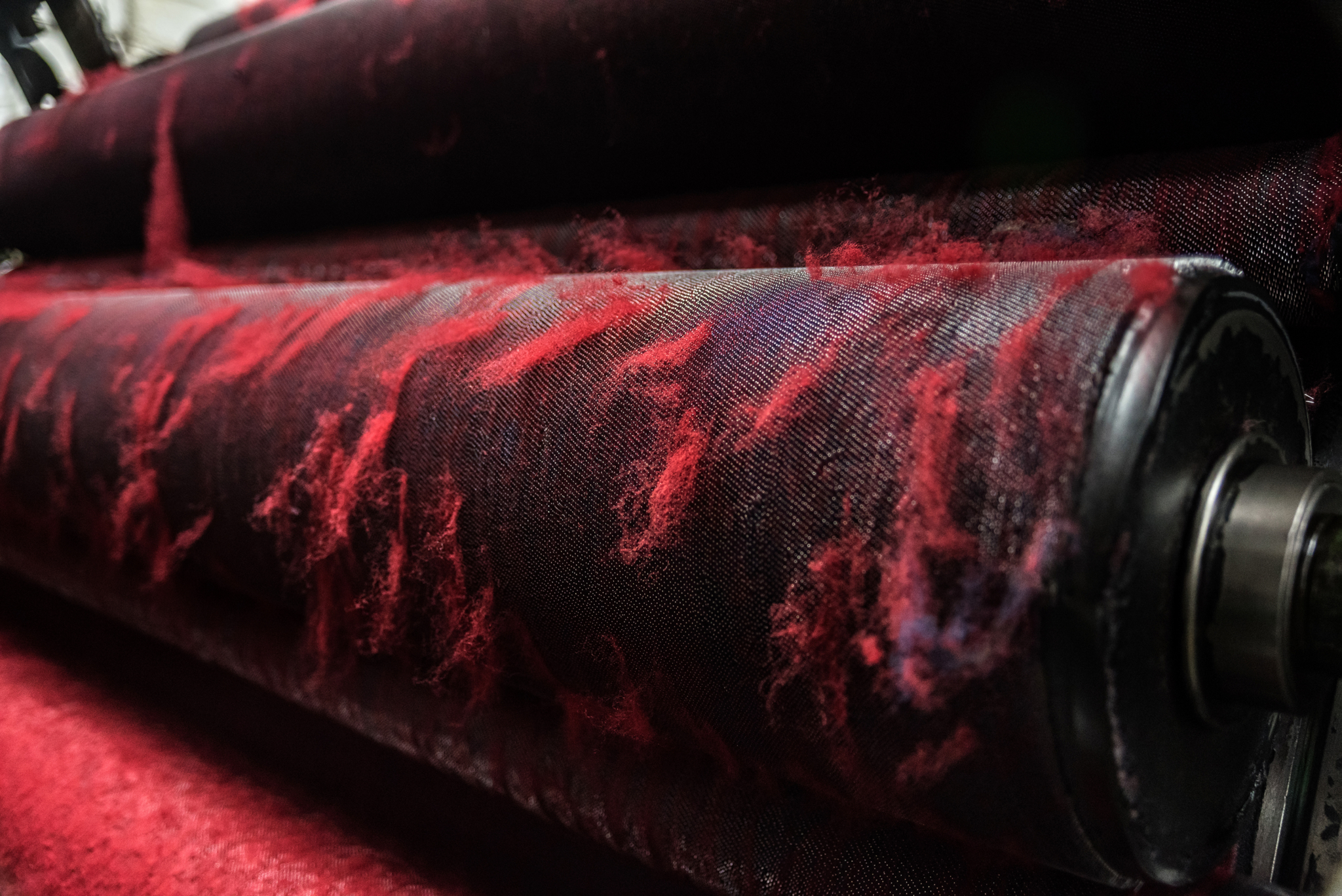

Rollers, combs and chains of Davis & Furber Woolen Card.

Single Horse Named

Jenny

Faribault Woolen Mill’s beginnings were modest. In 1865, Carl Henry Klemer, an immigrant from Germany, set up a carding-mill in Faribault, turning the wool of Minnesotan sheep into batting, stuffing for mattresses, pillows and quilts. That humble operation, powered only by a single horse named Jenny, eventually became the celebrated Faribault Woolen Mill we know today. It began spinning and selling yarn in 1872 and weaving in 1877 when it made its first blanket. After a fire destroyed the original mill, the Klemers built a two-story building along the Cannon River and moved their company to its current location in 1892. Suffering five fires and many floods, surviving the Great Depression and two World Wars, the resilient Klemer family, joined by the Johnson family in 1912, owned and ran the mill until it was sold to the North American Heritage Brands in 2001. It was the end of an era for Faribault.

With this new ownership, the mill lost its family spirit for one, then North American Heritage Brands went bankrupt and shut down the mill in July of 2009. Fifty people lost their jobs and the abandoned mill was a heartbreaking sight. The mill’s equipment was about to be shipped to Pakistan by a liquidating firm when Paul and Chuck Mooty stepped in and bought the company on a leap of faith.

Coming from Minneapolis, the two cousins, one an attorney and the other a businessman, first visited the mill in March 2011. The basement was flooded and the whole building needed extensive repairs. Looking beyond the mess, however, they were moved by the history of the old mill and felt its story might continue. After nearly two years, the mill opened its doors once again on July 5, 2011. It started out with only five people but by the end of the year, there were about forty workers, many of whom were former employees rehired by the Mootys. Order had been restored in Faribault.

Woven fabric for the Foot Soldier Military Blankets.

Made Under One Roof

Faribault Woolen Mill is one of the last vertically integrated woolen mills still operating in America. Raw wool is processed into yarn and that is then woven into fabric, all in the same building. Paul Mooty explains that it is just common sense to keep the whole production line at the mill. He can interact with the workers at every step of the process. “Our primary goal was to revive a U.S-made product that would ultimately contribute to create new jobs in Faribault."

“The old equipment is still running and is part of the charm of this place. We purchased newer, but used, additional looms and one used fulling machine. We bought brand new sewing machines for the finishing department, but the building itself was the major undertaking. Some of our windows are 120 years old and have to be replaced and we’re planning to build an earth-bottom along the Cannon River to mitigate flooding and protect our building when the river rises.”

The Faribault Woolen Mill was officially listed as a historic place in 2012 by the new owners. The picturesque reflection of the red brick building in the still water of the Cannon River embodies the enduring legacy of the mill. The quiet strength of artisanship and traditional manufacturing are the foundations of the Faribault blankets. Their durability and coziness turned them into cherished heirlooms, rich with family memories. They were lifelong companions, at times even life savers.

To enjoy the full story, become a Member.

Already a Member? Log in.

For $50/year,

+ Enjoy full-length members-only stories

+ Unlock all rare stories from the “Moowon Collection”

+ Support our cause in bringing meaningful purpose-driven stories

+ Contribute to those in need (part of your membership fee goes to charities)

EDITING: COPYRIGHT © MOOWON MAGAZINE /MONA KIM PROJECTS LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

PHOTOS & TEXT: COPYRIGHT © ANNE LAURE CAMILLERI. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TO ACQUIRE USAGE RIGHTS, PLEASE CONTACT US at HELLO@MOOWON.COM