I believe that Diane Barker was a Drokpa nomad in her previous life.

Her friendship with the nomads which span over two decades, her continuous journeys to their land,

and her deep affinity for their cultural and spiritual legacy manifest themselves in her words,

spectacular documentations, and humanitarian work to improve their plight.

Diane is currently working on a book that celebrates the contribution of nomadic life

to the sacred ecology of eastern Tibet. And this story, as part of that broader research,

reveals a mystical existence that is so integral to this rich culture.

– Mona Kim, Founder of Moowon Magazine

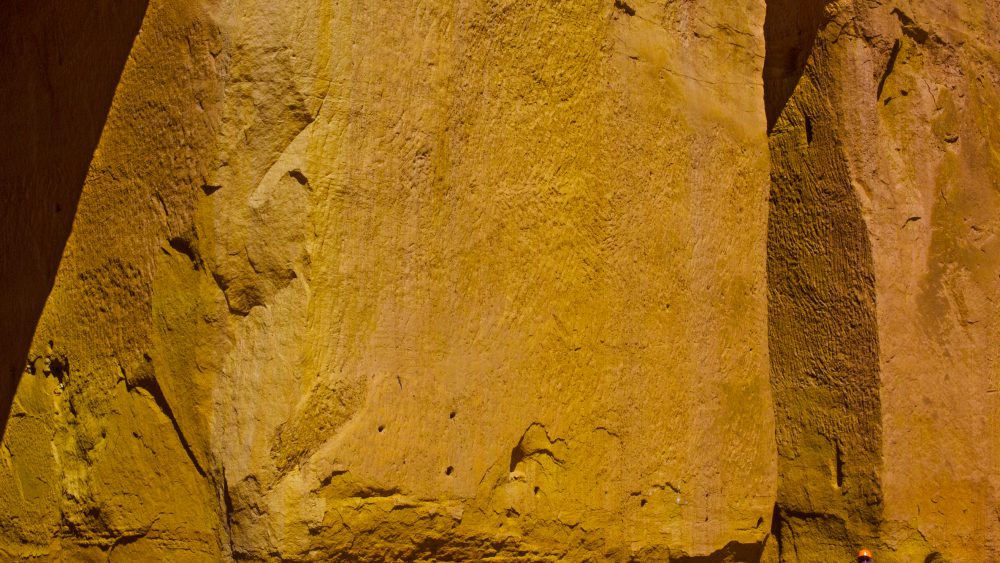

Tibet is a sacred land, its people an expression of that sacredness. For 17,000 years before Buddhism arrived the nomads and farmers of Tibet practiced Bon Shamanism which revered the land and related to it as a spiritual being. The sky, mountains, rivers, and lakes were animated by gods, demons or nature spirits. Bon ritual involved the harnessing, use, or subjugation of the natural elements in order to create and maintain a living balance between the natural and supernatural.

The establishment of Buddhism in Tibet in the 7th century transformed the country. Buddhism absorbed many Bon practices and created a culture of tremendous depth and richness. The people of Tibet held devotion for the sanctity and power of natural places. Today, shamanic practices continue to coexist alongside studious monasticism and a lived compassion for all beings.

What does this ancient world-view mean for the future? As traditional Tibetans hold the understanding of a sacred landscape, they bring reverence, care, and respect to the land. This is a natural attitude of stewardship, the basis of conservation and environmental protection.

"Nomads believe that a person's life force is connected with a locality and the spirits that dwell there and that a deterioration of this bond can have negative repercussions."

(From Drokpa : Nomads of the Tibetan Plateau and Himalaya by Daniel J Miller)

Environmental scientists have recently acknowledged that this traditional approach can make significant contributions to protecting endangered species and conserving biodiversity. What is needed now is not just a return to respecting the land but respect for the knowledge, skills and wisdom of those who have done so for millennia.

Prayer flags reflected in water in the nomad grasslands of Hongyuin, Amdo.

Traditional Tibetan culture knows the outer world as a reflection of the inner world; its values and practices connect the two so that they can nourish each other. Nature is alive with deities and spiritual energies. Sacred sites throughout Tibet are revered as places where these worlds meet, where the separation between inner and outer, spiritual and material, is especially thin. Mountains such as Kawa Karpo in Kham and Amnye Machen in Amdo, springs, lakes, relics, forbidden areas, places associated with spiritual figures (such as Guru Rinpoche,) and pilgrimage routes are respected as sacred. Hanging prayer flags, burning incense (usually Juniper branches), and saying prayers are just some of the traditional ways of honouring sacred sites. These practices protect the areas and their special deities, benefit the Drokpas, their grazing land, and their livestock.

To enjoy the full story, become a Member.

Already a Member? Log in.

For $50/year,

+ Enjoy full-length members-only stories

+ Unlock all rare stories from the “Moowon Collection”

+ Support our cause in bringing meaningful purpose-driven stories

+ Contribute to those in need (part of your membership fee goes to charities)

EDITING: COPYRIGHT © MOOWON MAGAZINE / MONA KIM PROJECTS LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

PHOTOS & TEXT: COPYRIGHT © DIANE BARKER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.