It is sometimes hard to imagine that a goat foraging on the desert-like terrain of Changthang can lead to the creation of one of the most exquisite and finest of the world's textiles – the Kashmir Shawl. In the words of a nineteenth century British administrator, this shawl "is the product of a felicitous conjunction between pashm, one of the finest animal fibres ever put to the loom and the amazing and unique skills of Kashmir's spinners, weavers, designers, dyers, rafugars and a host of other workers".

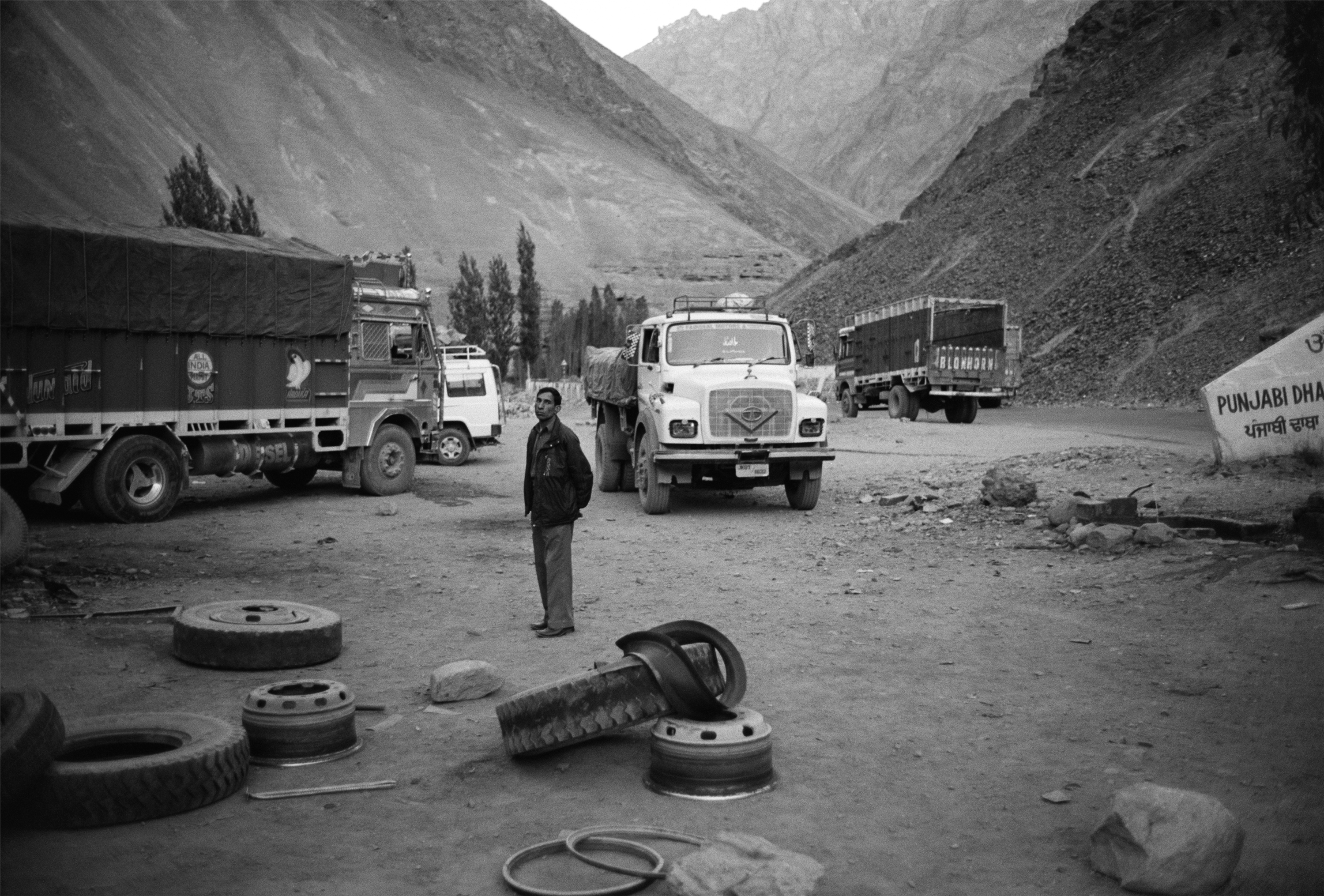

The story of the Kashmir Shawl continues in much the same manner today, but most accounts start the story in Srinagar, making no more than a passing reference to the fact that the some of the finest raw material in the world comes from the high mountains of Ladakh. Though both regions are located in the North Indian state of Jammu & Kashmir, and linked through the trade and manufacture of pashmina, making the journey of the story from start to finish important. It takes one through some of the highest motorable passes in the world and some of the toughest living conditions.

The following documentary film "Pashmina Road"

by Errol Rainey and Isaac Wall for ZEZE Collective,

is a meditative visual story that spans from Ladakh to Kashmir

to chronicle the elaborate process

from sourcing, to making of end pieces.

( Duration: 22 minutes )

Ladakh. In the summer months Changra goats are herded to lower altitudes where they can graze on pastures growing along the glacial rivers and streams. One Changra goat will harvest roughly 120 grams of raw fibre. Of that, only 70 grams will be fine enough to be spun into pashmina yarn. Male goats yield approx. 300 to 400 grams of pashmina, females 200 to 250 grams. Of that about 100 grams (200 for the males) can be used for weaving. Goat hair is also used for weaving other products so there is no wasteage. This wool forms part of the thick winter fleece the goats need to survive the harsh winters. For centuries the Ladakhis have harvested the fibres in the spring and traded with the Kashmiris, who then use the superior wool to create the finest shawls in the world.

To enjoy the full story, become a Member.

Already a Member? Log in.

For $50/year,

+ Enjoy full-length members-only stories

+ Unlock all rare stories from the “Moowon Collection”

+ Support our cause in bringing meaningful purpose-driven stories

+ Contribute to those in need (part of your membership fee goes to charities)