Crystal prisms, bronze, and light merge and interact in spectacular sculptures of light better known as chandeliers. Called lustre in French, the word qualitatively signifies radiance, brilliance, excellence, and glory. Aside from its function as a source of light, chandeliers were historically conceived for churches, palaces, and residences of the wealthy to symbolize—and communicate—power and social standing. Chandeliers were objects of passion and works of art in the past and continue to be today.

In France, the savoir faire behind chandelier making had almost been abandoned and forgotten, partially due to its complexity and a decline in demand. However, in Hameau des Sauvans, situated near Gargas in Provence, a man has revived this unique trade, breathing life and innovation back into the art of creating these magnificent objects of light. He imagines, restores, and recreates the grandest and most complex jewels of all. In one sense, he works alongside the grand masters of centuries past, serving many kings and queens such as Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette.

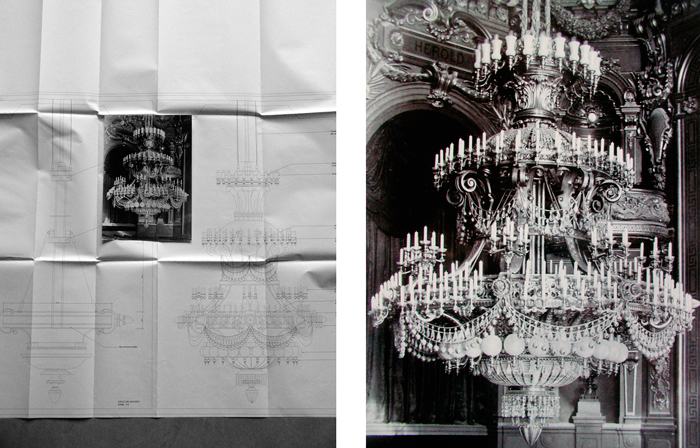

Régis Mathieu, the name and the brilliant creative force behind Mathieu Lustrerie, considers himself a lustrier-cum-bronzier d'art (chandelier maker- cum- bronze artist). A native of Marseille, Régis possesses an uncommon versatility and virtuosity as an artist, entrepreneur, collector, and restorer. He is also an impassioned traveler with one foot in India, one foot in Moscow, another in Paris, and yet another in New York. Yet all the inspiration, commissioned projects, raw materials, and discoveries from these distant lands ultimately culminate in what he calls his "playground"—aka his atelier in Hameau des Sauvans. This is where everything merges. This is where he and his team of 25 artisans par excellence research, restore, invent, re-invent, reproduce, test, draw, mold, cast, cut, heat, melt, patinate, polish, assemble, catalog, and archive these grand-scale splendors. And they are commissioned by none other than the highest of cultural institutions such as the Louvre, Opera Garnier, and the Trianon, as well as clients who seek works of art. Meticulous attention to details, impeccable quality, and making the impossible possible are the central tenets of Mathieu Lustrerie. In this sense, Régis is the Steve Jobs of his trade.

To enjoy the full story, become a Member.

Already a Member? Log in.

For $50/year,

+ Enjoy full-length members-only stories

+ Unlock all rare stories from the “Moowon Collection”

+ Support our cause in bringing meaningful purpose-driven stories

+ Contribute to those in need (part of your membership fee goes to charities)