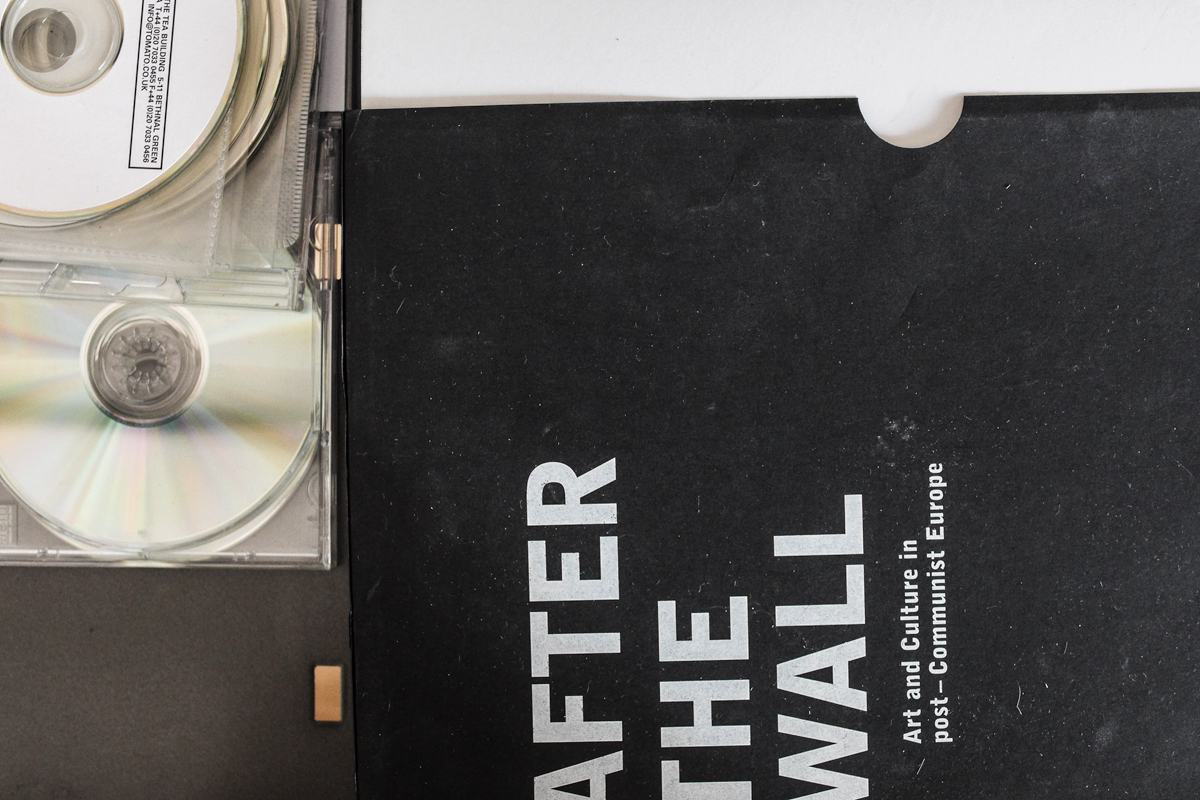

New York, 1990s: In a bookstore, I encountered a mysterious grey book with no cover image. Nothingness, except for the words "process", "project", and the name of a fruit. The inside pages were just as cryptic. But the book has been with me ever since, as a reminder of creativity that goes against the grain of the times. Today, Tomato's studio on Baltic Street has become my habitual stop-in point on London trips to catch up with (and be challenged by) my friend and colleague Simon Taylor. In a recent trip, I stopped in a bit longer to do a proper probing of this unique group of "visioneering" men, whose fascinating approach to "making" will inspire those who "make".

– Mona Kim

With an open mind, resilience and intensity in how they approach "making," Tomato balances that line between the use of today's technology and craftsmanship. And how they manage the pressures of commerce while holding fast to their ethos is an interesting example especially in the complexity of today's world. It poses the question, whether artisanship is as much about the approach as it is about heritage.

Tomato is a collective initiated in 1991 by a group of dissatisfied creatives during the London economic crash of the early '90s. Back then the pub was the Facebook of its day and a place where hotbeds of conversations revolving around creativity, process, and everything else in between transpired. The life of the studio would spill into the Georgian pub located at the end of the street, and most of its members would spend so much time there that even phone calls would be redirected there.

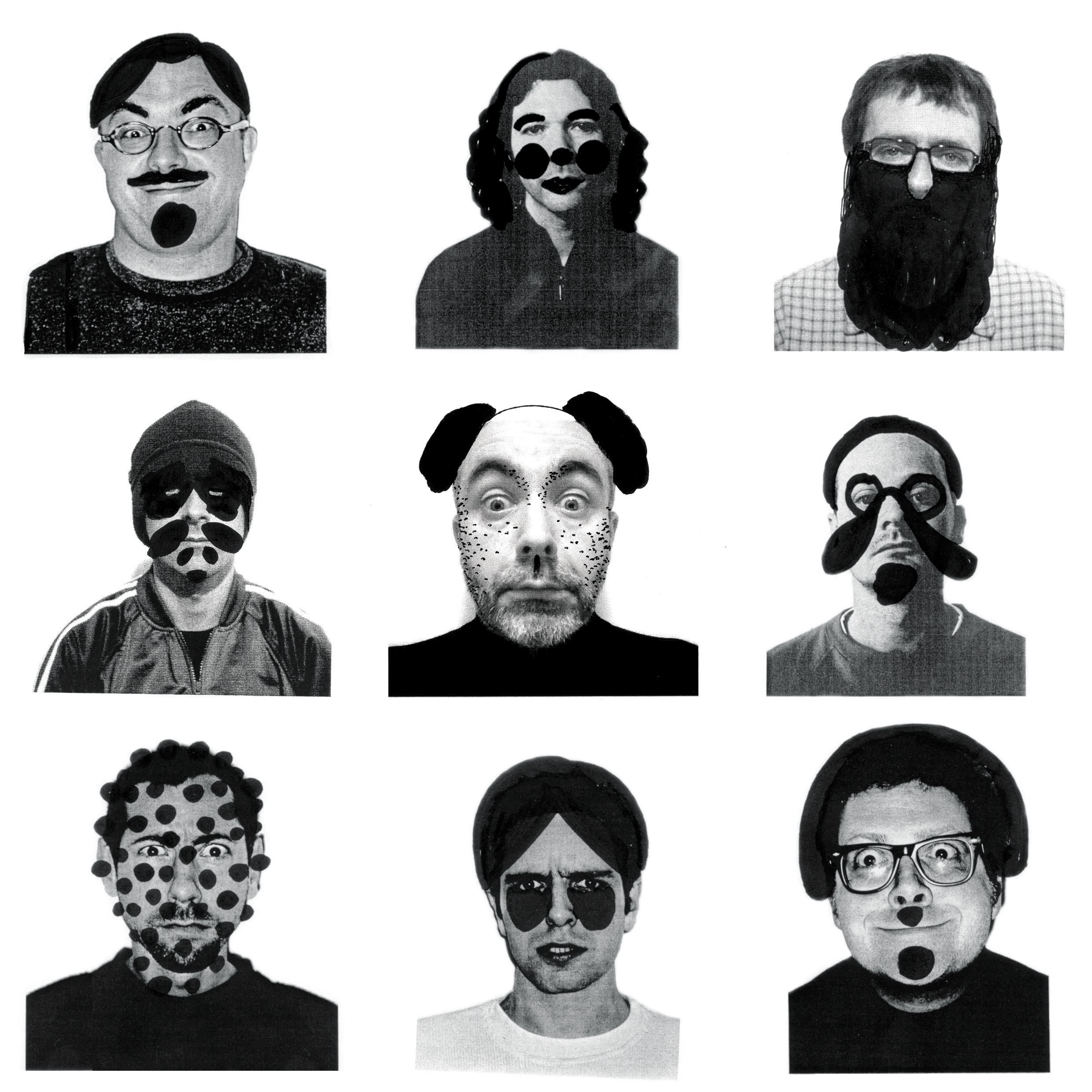

Though the title of their story is purposefully tongue in cheek in tribute to their wry sense of humor and self-derisive bantering à la British, it also describes their unique approach to their work and aspects of artisanship that we may not have considered. Meet Simon Taylor, Michael Horsham, and Dylan Kendle of Tomato. (And please mind the gap between questions posed, and answers received).

Making, Thinking

MOOWON: Your work always seem to straddle both the technology of the times and traditional techniques.

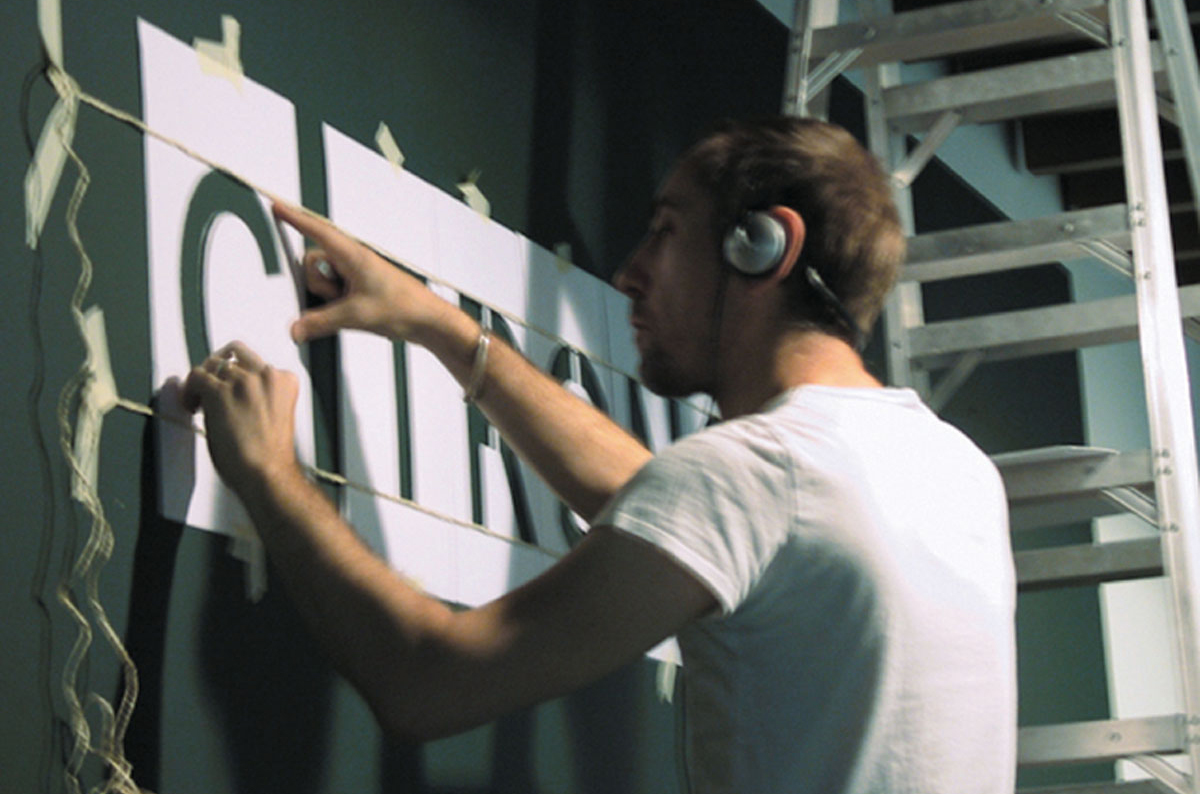

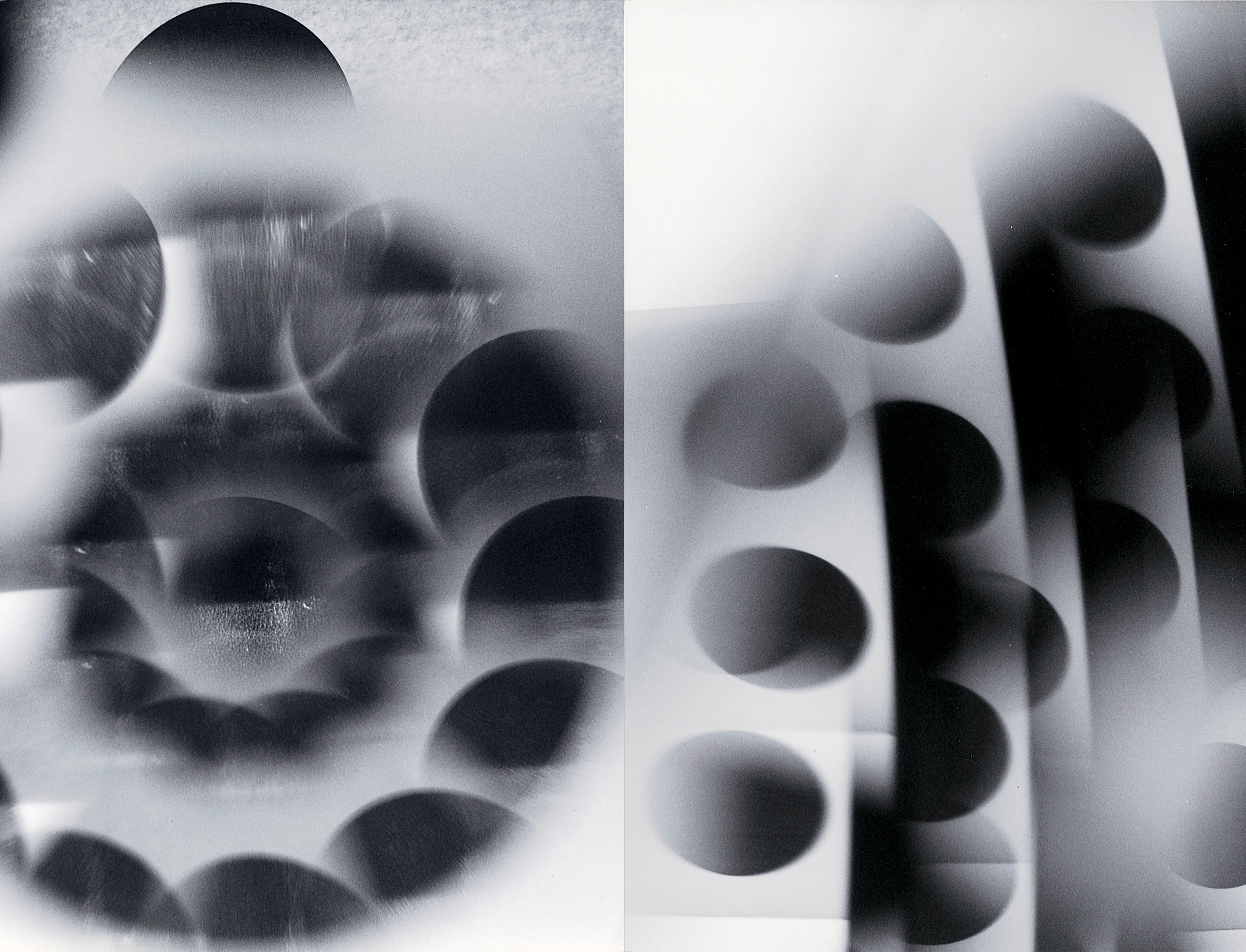

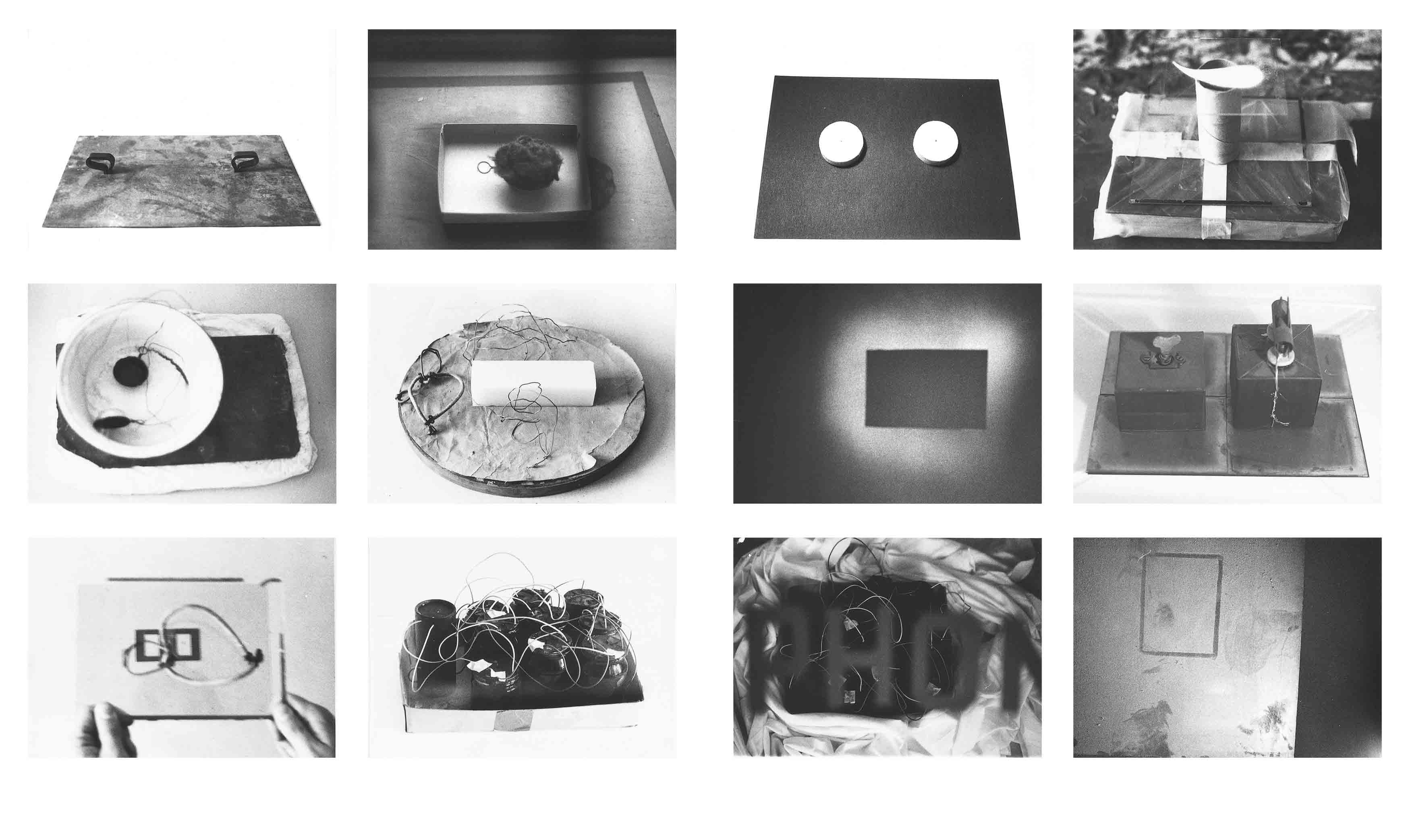

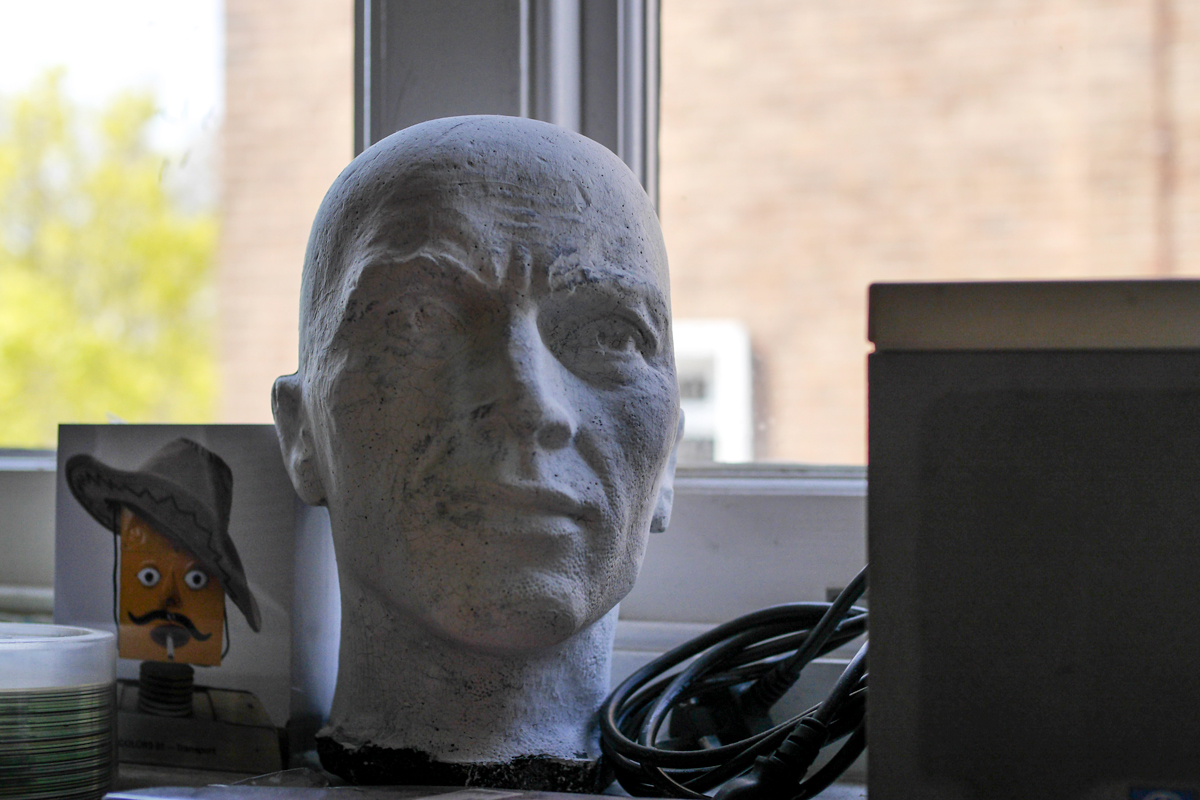

SIMON TAYLOR: Making, as part of the process, was always at the heart of our work. Making, then seeing what comes from that. Richard Sennet in his book The Craftsman describes a process and method that craftspeople use, as a way of improving upon what they do and to share what they're doing with each other. That whole thinking-making-making-thinking is what we've been doing. Because we've worked so much as a group, we share process and knowledge. In other words, it's collaboration. (A tiny wry smile from one corner of the room)

MOOWON: Ok, Michael, I see that you want to say something. Just come out with it.

MICHAEL HORSHAM: The choice to take or not to take, or to share or not to share, is always in flux. It's quite interesting. It waxes and wanes, but it's always there. And it's that continuity we had over a long period of time that is one of the most valuable things. But I made that face when you (points to Simon) decided NOT to share.

SIMON TAYLOR: Its funny, I didn't SEE your face, but I could HEAR it.

DYLAN KENDLE: It disturbed me to the bones.

MOOWON: Do you guys always talk in duplets? So, it's even less about the end product?

SIMON: Yes. It is very much less about the end product. Though we do care about what we put out in the world, what's important is the act of making.

MICHAEL: There's something highly satisfying about finalized pieces as well, in the sense of moving your focus to something else afterwards.

DYLAN: Investigations and experiments that are going on in a project sometimes overlap with a new one that comes through the door because you are exploring similar ideas, or the technique or materials are appropriate to them as well. Other times, you just have to deal with it in parallel. But the thinking process that is happening on a more experimental project always informs your responses to the other commercial project on hand. And for me, this on-going research and questioning that happens in the background is what differentiates our way of working. Commercial work is important to keep the studio going, and it exists in parallel, but it is much less important to personal development.

SIMON: True, but to add to that thought, I also think that a commercial project can impact how I'm thinking about more personal or non-commercial projects. It's just a matter of being open to it, rather than having an expectation of what you think a project is.

MOOWON: Open. Since I've known you, Simon, that word has always been ever-present. You've also mentioned the ethos of the studio. What is that exactly?

SIMON: We've been giving talks called "Research & Practice," which originated from a talk given at the White Chapel to an audience of tutors interested in how a professional studio or agency approaches research, and how that manifests itself in our practice. But I think we misheard it a bit and ended up doing a talk, which was about how, for us, research IS the practice. It is one and the same thing. Research isn't limited to visiting libraries or any of those traditional venues. It is something that we do all the time, and it can be the actual act of making. It's a rehearsal in fact. And what you're actually doing is rehearsing over and over again, and looking at its parameters and how they shift and alter; defining the parameters yourself when you don't have them; looking within them to see what can work and may not work, etc. Theater director Anne Bogart in her book A Director Prepares talks about how actors and dancers make their best work when they go beyond their comfort zone. That also applies to drawing, playing instruments, and other walks of life.

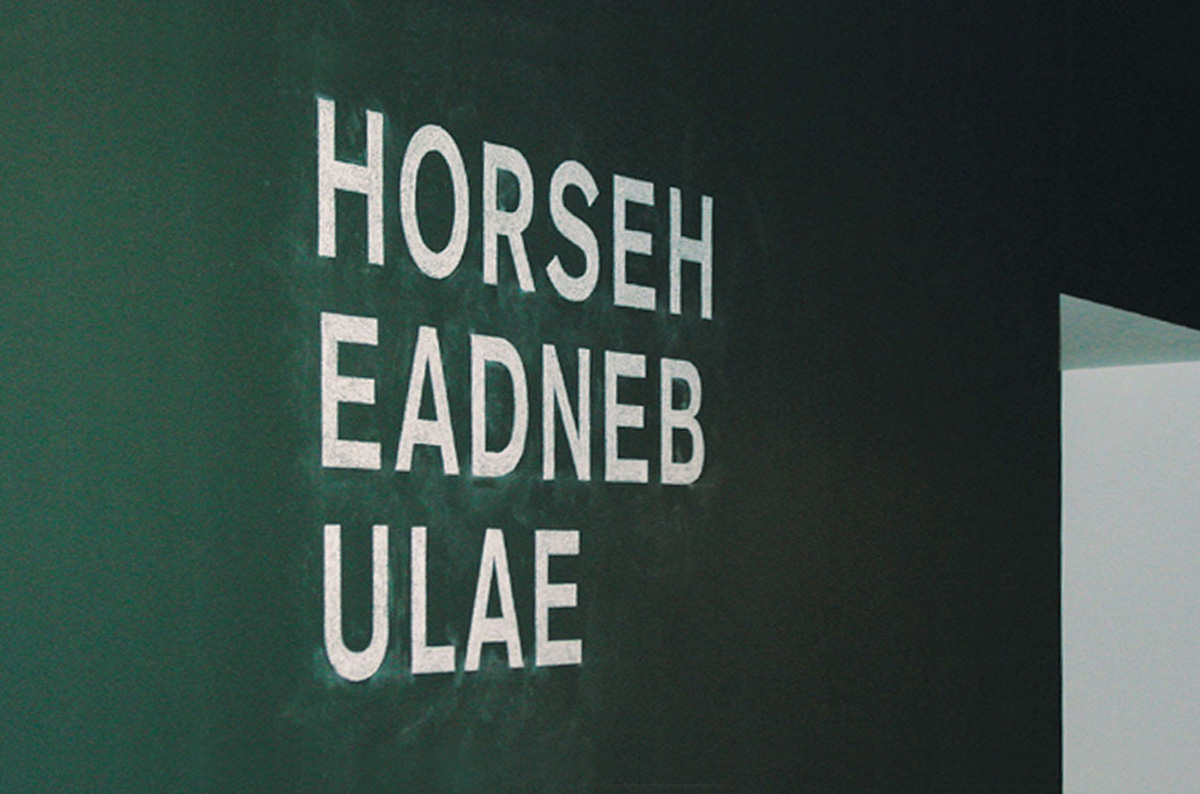

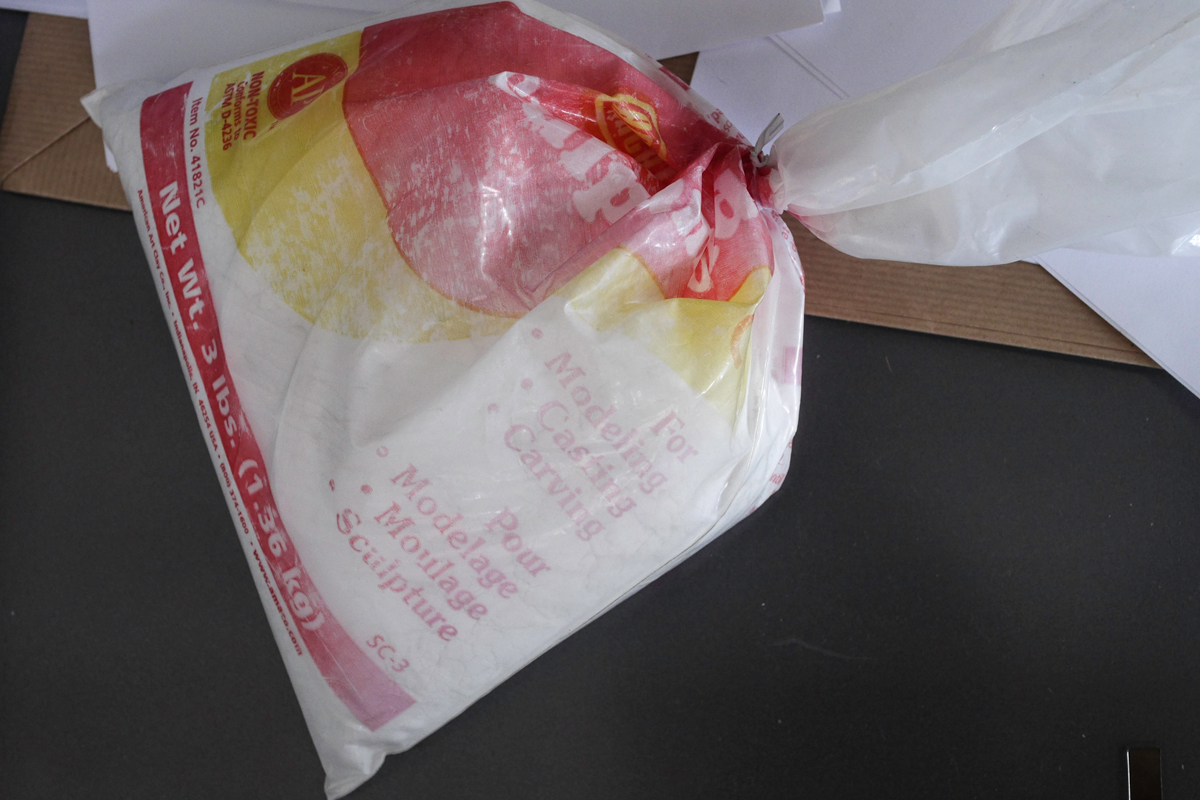

DYLAN: Often, for designers or studios and agencies, there are those familiar practices such as sketching out rough versions of an idea and spending the majority of the time refining a version of that one thing. For us, it's more about investigating the boundaries, whether it's software, materials, or a means of expression. This allows us to re-evaluate or question the brief. We tend to work in many different mediums, which allow us to be freer in our approach. This doesn't always make for an easy commission, but it's far more interesting and rewarding. It's less of a machine and that allows unexpected results.

MICHAEL: I think your stake in it is different than what it would be if in another setup.

SIMON: Authentic?

DYLAN: "Visioneering."

SIMON: Yes, Visioneering. Like "Dylan, what did you do all day?" –"Visioneering."

Not a Label

SIMON: There's a really big romantic idea going around at the moment globally, with everything from Kinfolk Magazine to expensive bread. My granddad was an artisan in the proper sense. That was their job, and they did it with pride. It is about skilled labor, craftsmanship, with a notion of authenticity tied to it…in other words, a sense of competence.

DYLAN: As in "competent" bread?

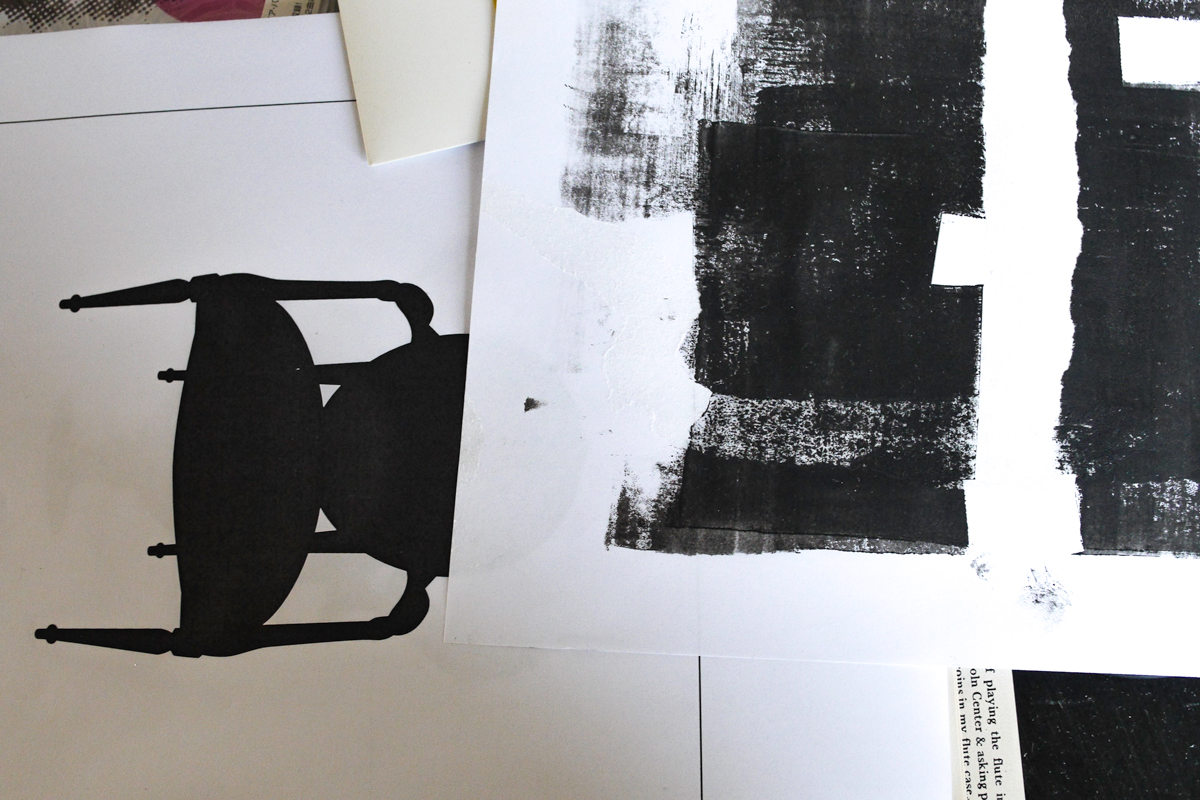

MICHAEL: It's "arts et métiers" (applied arts and crafts). It's making, it's a making skill. You claim that role by doing it, not by calling yourself that.

SIMON: I find it problematic when people ask me what I do, or what I am, because it's hard for me to answer that question through labels such as designer, artisan or creative director.

MICHAEL: I just describe the last thing I've been working on.

SIMON: Our work is more craft-based. To define ourselves as "artists" would not be comfortable for us.

DYLAN: Designer-maker.

ALL: "Visioneering"? (Poor Dylan)

SIMON: So the idea of crafts really does express the idea of think-make-make-think. It also expresses the process of doing and improving, problem finding, and problem solving. Design answers a question. Art asks a question. But what we're interested in here is what's in between those two things. You can be working away on something, asking many questions without immediately having an answer. And that's interesting. Isn't that what craft is?

MICHAEL: There's a brilliant book The Nature and Art of Workmanship by David Pye, where he talks about the idea of workmanship at risk. He's making something, and each stroke of the chisel or the gauge is in one way crucial and in another way a risk. If he gets it wrong, it would disrupt the process, and he would need to correct it again.

MOOWON: You are a commercial studio that managed to keep a non-commercial approach to projects. How do you do that?

SIMON: We realize that the commercial part is important for our livelihood. But that isn't what we're really about, which has to do a lot with the fact that we don't get repeat business (all laugh). Though it is a commercial studio, it is not a supply and service studio. So in terms of a business model and commerce, it's not ideal. But in terms of the creative side of research, and potential to create new things, it's the best model. And that's probably more at the forefront.

MICHAEL: Models are out there for commercial studios, but I'm not sure that the freedom to continue in the way that we do would be sustainable if we yield to commercial pressures.

SIMON: I think that would drain it.

MICHAEL: For example, if we had a sizeable staff that we had to take on and pay to do jobs that we nor they would like to do, that would not be a particularly healthy situation. We made a really conscious effort to make that less of a bind; we're for the lean philosophy.

MOOWON: What were some of your struggles? In classic design or advertising settings, overheads, internal politics, and the like, could be challenging. A collective is something, which by nature assembles distinct individuals—and this must come with its own set of challenges. What was involved in maintaining a group yet keeping the original ideology intact for over two decades?

SIMON: Tomato was born out of our dissatisfaction with existing opportunities that were quite limited in the commercial and creative industries. At that time in London, there was a terrible recession, and we were on the downward trajectory of a cultural explosion that had originated from the punk rock and new wave movements. All that disintegrated with London's financial collapse. In came the mind-set that time is money, and creative opportunities became even tighter and more conservative, which probably weighed on everyone's mind, So we wanted to create something freer that we felt could exist.

SIMON: One way was to have a collective where we could support each other and where anyone in it would be anonymous – a very egalitarian approach. We put that idea into practice and, after three years, we were surprised that it had become very popular.

But it was very difficult to get the collective up and running during those years. The notion of collective at that time was considered a bit airy fairy, something from the hippie '70s period, design squat, etc. But by going forward with it, we were able to prove that it was a better way of doing things. And we've been quite challenged by that over the years, of maintaining that sort of path. We had to constantly change the way we did things. For example, we learned a lot about group behavioral patterns.

It's very interesting how a group of 10, as opposed to 20, could be vastly different. A group of 40 would require a strong hierarchical aspect, yet another thing altogether. Some would call us naive, but that's certainly not what we wanted. We managed to work our way through it though.

MICHAEL: It has been an interesting trip.

SIMON: Certainly. And as individuals and as a collective, we had to learn what ego meant—and it was difficult to manage because creativity comes out of a very ego-driven place. And things like ego must be looked at and dealt with. Age and wisdom help. Also, struggle for me has less to do with overheads and frustration of internal politics. It has more to do with having opportunities to make interesting work in a commercial setting.

DYLAN: To do the "next thing" doesn't mean to do the same or similar thing twice. Clients are used to commissioning a portfolio of work that groups very similar things. But we don't really like making the same thing or close to the same thing twice. We've all made lifestyle choices to maintain that vision instead of running after the conventional goals of healthcare, pension, etc. But this type of choice is an expensive choice. When students envy that disposition, I don't think they realize the cost of it, or what that means.

SIMON: You do have to give up something.

MICHAEL: "Caged" by our freedom? That calls for a revised title: "Artisans of Baltic Street Caged by Their Own Freedom."

SIMON: Or "The Tragic Tale of Visioneers Caged by Their Own Freedom."

SIMON: We all recognize that this is a very bad business model. But that's not really the point. The point is to have this. Bottom line is that we cannot NOT make the work. We'd be unhappy if we were to point to others to do this, not be making the marks ourselves, and not create the work. This goes back to your original question of "why did you start Tomato?"

MICHAEL: That was a trip. If you look at the trajectory of the thing called Tomato, I wish I had kept a diary of the changes – dynamics, people, people we met, work, events. A really unpredictable journey, that's the only way I can express it.

SIMON: Yes, like that day when Dirk's dog bit the second richest man in the world. The Sultan of Brunei's brother came around to see us about designing a MC Hammer party invite for his niece. And Dirk's dog took a dislike to him and went for him.

MICHAEL: And there are many of those crazy stories.

SIMON: Or that day when Graham bought a BB gun without learning how to use it properly and came into the office and shot all the windows out by accident. We had to live that entire winter with holes in the window. Winter is very cold.

MICHAEL: David Bowie popped in with Iman about doing a book on her.

SIMON: The way it happened was that Brian Eno, whom we know…

ALL: Clangy! (Clangy = a slang to describe people who have a tendency to drop or boast famous names, also often used in Baltic Street for anyone displaying a slight symptom of such state)

SIMON: It's been sort of fun. It occurred to me the other day that this might be what we do…forever.

Tomato is a London-based collective established in 1991. It is a group of artists, designers, musicians and writers that creates cross platform, multi-media art and design projects, both commercial and research based, for national and international clients. Tomato also publishes books and artworks, creates exhibitions, gives live performances, and hosts workshops and lectures. The group has been at the forefront of award-winning work for more than two decades. And the collaboration continues...