Hazaribagh, the “land of a thousand gardens,” is one of India’s least known art paradises. A small district in the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand, Hazaribagh is home to many tribes and ethnic communities such as the Munda, Santal, Oraon, Agaria, Birhor, Kurmi, Prajapati, Ghatwal and Ganju. Unknown to most of the world, the women of the region have been painting their homes with beautiful designs for centuries, drawing upon an art heritage that harks back to the cave paintings discovered in the region. Two kinds of ritual wall paintings are commonly seen in most of the houses: the khovar associated with marriages and the sohrai with the harvest. The women artists create verdant images of flora and fauna, literally transforming the villages into a land of gardens. These art forms are not just expressions of beauty and creativity but are also important means of transmitting cultural values.

Khovar which literally translates into bridal cave (Kho means cave and var is the bridal couple) is the name for special murals made during weddings. This is a type of sagraffito art using the “reversed slip” pottery technique. This technique consists of applying a base coat of black clay on the earthen walls of the homes and letting it dry. After it is dry, a wet slip of creamy white earth-coloured kaolin is applied to the wall. Working quickly, the women use four fingers of their hands or a plastic or bamboo comb to scrape out designs on the wet clay. Flowers, birds, and magnificent beasts—including tigers, deer, cows, oxen as well as anthropomorphic motifs—come alive on the walls. The underlying black clay which is revealed as the design is drawn in sharp contrast to the white clay, and the comb markings add a further layer of design and complexity to the mural.

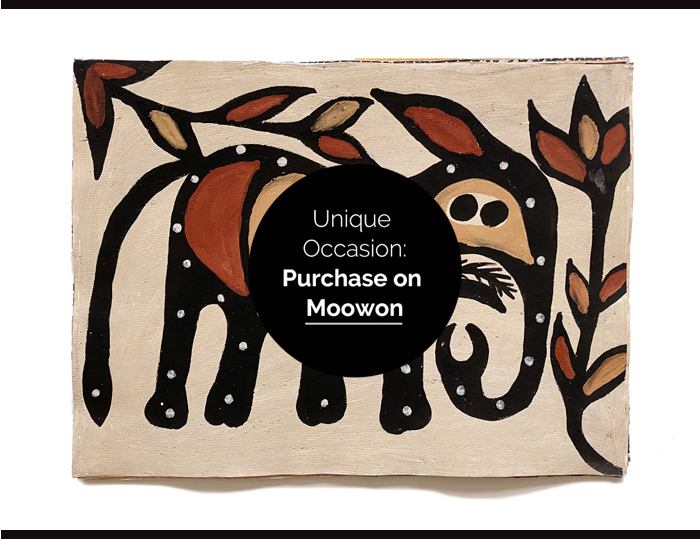

Sohrai is an art form associated with the winter harvest festival celebrated one day before Diwali (festival of lights) in winter. Women use earth colours such as red ochre, yellow, and black to create Sohrai murals depicting Pashupati (lord of animals), Kamla baan (forest of lotuses), and Tree of Life as well as multiple animals and birds. These murals are painted on the walls using cloth swabs or the chewed twigs of the local Saal tree. Many of the designs may be compared with the prehistoric rock art, pottery markings, and prehistoric seal motifs from Harappa.

Today, the Sohrai and Khovar art traditions are under threat of perishing. In the interest of being a "developed" nation, the Government of India is committed to providing permanent brick and cement houses (pucca houses) to replace those made of mud and wattle (kuccha). The brick houses do not lend themselves to being painted with clay colours and, as a result, these art forms are disappearing.

of Tribal Consciousness

At the genesis of tribal art is the ageless tradition of wall art that is part of the ordinary lives of the women painters of Hazaribagh. They are still visible today in their myriad forms: prehistoric rock paintings, huge sacred and secular wall paintings and decorations, the decorative symbols of the festival of lights (Diwali), and the marriage room or Khovar. Their art is the language of signs that conveys meanings, traditions and messages from the past.

Being the earliest form of expression, earlier than the pictograph or hieroglyph, these wall art symbols predate script and have parallels elsewhere in the world, although perhaps nowhere else is it still a living tradition. Painted by simple village women, who have never been exposed to photographs nor pictures depicting the rock art of afar their work hauntingly resembles those of faraway tribal societies, some even in other lands. They have not been exposed to modern artistic forms such as surrealism, and they know nothing about the genius of “primitive” art. Ritual and mythic in content, traditional forms known to earliest man and dating back even to the Mesolithic period—human, animal, bird, fish, and plant—emerge through their art.

The style changes imperceptibly from village to village. Although the tribes appear in their individual tradition through their art, they are bound together, and form a mosaic of the region’s rich tribal history.

Their art is an overflowing stream of symbols, designs and images which are connected both to the prehistoric rock art and the tribal folklore of Hazaribagh and its environs. But within these parameters, the enormous creativity singular to each artist is displayed, making these paintings individual works of art in the truest sense.

The women painters have repeatedly displayed imagination and virtuosity in creating the primeval, the fantastic, and the bizarre in an endless repertoire of forms and combinations. They are inspired with such originality in their work that they cannot even copy their own pictures!

What is before us is not mere collective creativity; it is the flowering of individual genius in a collective, artistic, and emotional tribal consciousness.

Kinship

and Secret Meanings

For the tribal, Man stands at the apex of the biotic pyramid, but not without support from Nature

who forms the great pyramid’s base. The tribal religion (Sarna worship) exalts nature and its proclivities lead it to animist worship of waterholes and land formations, as well as the Sacred Groves (Sarna) which represent the deities of the forest. The tribe’s Ancestors are the spirit of the tribe in the other world, an ageless soul (Purkha). The Burial Ground (Pathalgara) represents the deities of field and stream, of carefully cleared cultivable lands (Bhuinhari lands) which the tribe’s ancestors first cleared from the forest (Khuntkatti Rights) to make the Earth their mother more productive.

Within this religio-cultural milieu, in which Nature was the chief partner, the tribal year was born in two perfect halves, the two major seasons: the marriage of nature and sun, man and woman, which created life; the harvest of grain and domestication of wild cattle which created a civilization built upon kinship for man. In its artistic form, the former, the season of Hunting and Marriage, is symbolized in Khovar; latter, the season of Planting and Harvest, in Sohrai. During this time, in the forest hamlets all over the Hazaribagh jungles, the tribal women draw inspiration from these great natural forces around them and paint remarkable masterpieces depicting birds, animals, and fishes of the Khovar. Hor (man), incarnated in Sohrai, is the season of man when the harvest and cattle are celebrated in the winter during Diwali.

A tribal painting, or even a single object, tells an entire story to those that know it. It speaks to the racial memories, familial connections, and experiences of a people, a tribe, or a family. The keepers of the secret meanings are the tribals themselves, who over generations have derived profound meaning from their evolving perceptions of these symbols and have connected those with the rituals and seasonal cycles they celebrate. The connection must never be allowed to die as it is perhaps one of the oldest intact ritual symbol traditions in the world. In tandem, the appearance of new symbols in this living art form continues in a process of absorption and change.

Origin, Tradition, Rituals

The original event which began the tradition of wall painting, the Khovar, has been lost in the mists of time. The idea of bridal caves was probably a development of the post-cave dwellers. . .The “bridal cave” art tradition began because the bridal couple was sent out to the forest to spend the nuptial night. The couple observed the painting of those cave symbols in the Khovar and drew the same within the house.

Today, these “marriage rooms” are decorated with bird forms, such as peacocks and doves, and plant forms such as betel leaves and the date palms, and are painted by the women of the family, chiefly the mother Devis and elder sisters. From the Khovar room, the bride leaves her mother’s home and is received in her husband’s house. She brings with her the designs which she had learned from her mother and aunts in the home village. From her mother-in-law she learns designs particular to her husband’s village.. Thus, a flowing tide of design forms continues.

For the tribals, nature is the producer of ancestor spirits. It is for this reason that ancestor spirits are revered and propitiated in all their manifestations: No tribal worth his salt will eat or drink until either a grain of rice or a drop of liquor is first sprinkled on the ground for the ancestors. These traditions are passed on to children at a very early age.

The painting of the Khovar tradition is one of such traditions which a mother (or aunt) passes on to her daughter, who in turn learns the traditional forms of her mother-in-law’s house. The influence of the woman in tribal society is strongly enriched with matriarchal overtones. Tribal society believes in the earliest human tradition of Earth Mother, which reveres the woman as Mother: the medium and the vehicle of life, the one who has power over life, the one how has power of creation through birth. The Khovar tradition is thus a woman’s birthright, and creation is for her both a natural and sacred act. This is at the root of Hazaribagh’s Khovar painting tradition.

The inner rooms kept for marriage khovars (bridal rooms) are left unpainted until February or March, when the wedding season commences. Shortly before the wedding, the bride’s mother and aunts, and sometimes elder sister, will paint the bridal rooms during these months because it is a favorable period. Ritual hunts take place at this time. The peacocks are also in nesting season and so depicting them with their young in khovar paintings is considered an auspicious omen. Because the winds start to blow during this period, the painting work is done during dawn so the light coat of earth to be cut won’t dry too quickly. Generally, these rooms are given a black coat first and then covered with white earth and then comb cut to reveal images of birds, animals, and medicinal plants.

At this time, the cries of the peafowl, revealing expressions of fulfillment, fill the forests. The women plan their clay canvases well in advance, but timing is dependent on the marriage patterns that are subject to astrological predictions. The marriage season ends in March with the festival of colour (Holi, Phagu), and house repairs continue in April and May before the rains start in mid-June. The young bride is called upon to demonstrate her ability in these repairs (Ghar Potna) in the blazing summer heat. After the rainy season starts, the attention of the women turns to rice cultivation, and during July and August they are busy transplanting paddy which will be harvested in October.

Rituals, Colours, Techniques

Sohrai is the art of the women of the Kurmi, Santal, Munda, Oraon, Agaria, Ghatwal tribes and is also connected to the region’s rock art as well as Ganju art. An evolution of Khovar painting through its contact with Manjhi (Santal) house decorations in eastern Hazaribagh, it is a direct method of painting and uses the kuchi (bruised stems) of the sakhua or saal tree, both indigenous to the region’s jungles. One of the striking features of this art is how the bodies of animals are divided into compartments and painted as seen in pre-historic rock art.

The Sohrai festival celebrates the rice harvest and is specifically sacred for village cattle. It is a day to garland the animals with sheaves of unripened paddy, to anoint their horns and hooves with the prized Dori oil that has been extracted from the seeds of the Mohwa tree, and to put on red vermilion (coveted symbol of the married woman in India) to mark ritual. Forms of oxen and rams that “hold the whole world” on their back are painted on the house walls. Sometimes we find an anthropomorph, a ritualized yantra, or a geometrically hermetic form that represents a male deity (Shiva, Pashupati, or Ram) guiding the animal. Almost always, they are depicted standing on the back of the animal and wearing a headdress. The elephant is another animal often depicted in Sohrai paintings. Its multiple representations in Sohrai (and Khovar) has been present long before the idea of Ganesh was created.

The festival takes place during the early winter in October to celebrate the return of Lord Ram from his long forest sojourn. The cattle in Sohrai art is significant as the tribals believe that Lord Ram brought back with him domesticated wild cattle and also gave them herds of kine for milk and oxen for the plough.

In the morning of Sohrai, the cattle are all sent out from the village to graze in the jungle. Once they have departed, the women and girls begin to apply the white lines around their votive drawings, adding the them to the concentric circles in the animals’ bodies. The white color is made from a paste of rice flour mixed with milk and water. The white aripan paintings , on the village paths leading into the various houses, is made by the women of the village on freshly painted mud floors. They pour rice paste gruel through the palms of their hands after collecting it from a bowl. This is accompanies by a séance. The mixture of earth and cow dung is then applied with a broom or by hand. As soon as the cattle come out of the jungle, they are bathed at a nearby pond or a stream before they are welcomed back into the village. The cattle trample over the sacred aripans adjoining the houses.

The triple lines of color which outline all forms of Sohrai is of immense significance. First of all, the form is drawn freehand on the mud plastered wall by using a long nail to scratch a seminal line into the mud. Then, a double red line of liquid color is applied with the bruised stem (kuchi) on either side of this. Next, a black line is applied with the double red line to fill in the background space. After this, the drawings are left unfinished until the very day of Sohrai. On the morning of the festival, after the cattle have been sent out to the jungles, the women and the girls begin to put in the white. The white lines cover the outside of all the red lines. In the meantime, older women busily make the white aripans on the floors to welcome home the cattle. The white outermost circles, sometimes made from clay diyas (lamps) and used for stamping colours, are added into the spaces of the animals’ bodies.

The colors also carry meaning. The red line is drawn first to represents blood as in life; procreation and fertility; marriage as a scared state; propitiation and sacrifice; and the red earth of the Gerua field. The next line is black, which alludes to the eternal dead stone of Shiva, omniscience of Death, in the trefoil pattern of the moving line. The all-encompassing outer line, the white sheath of Life and Death, stands in its traditional values of protection, fidelity, chastity, grain, and milk for the forest communities of India. Sohrai art is a celebration of a good harvest, the abundant fertility of livestock, as well as family and community.

The contact of Sohrai with Santal art throughout the forested watershed of the Konar river in Hazaribagh has resulted in a unique style of purely glyptic art. The painters leave the yellow earth plaster of the walls unpainted, while they cover the area outside the form that is represented with a heavy liquid-pigment using their palms and fingers, more like alpana painting. Striking earth reds and blue-greys on the particular ochres of the walls resonate the colors found in the soils of the hilly terrain in which the Santals dwell. It is as if the geochronological expression of the environment has entered the ritual art as another one of the countless faces of Shiva.

Tribal Heritage

The tribals believe that their art form is born naturally out of a way of life, a unique value system, and the tribal approach to life. The remoteness of their villages and the lack of communication and transport facilities over the rough, river- intersected hilly terrain has had a direct bearing upon the preservation of their age-old culture and way of life.

Missionary activities in the tribal regions in recent history have greatly affected the traditional culture and lifestyle of the tribal people. This exposure to the outside world, its westernism, and the globally dominated market economy has imparted new meanings to ancient symbols causing the tribals to unfortunately lose faith in their ancient traditions and value system. Universalism has been the greatest threat after nationalism to the continuity of the tribal world. For example, the Christians have attempted to shape the religion of the Sarna tribals to its own vision, and the Hindus have done similarly. This is the tragedy of a root culture.

On a socio-economic level, there is a threat to the continuity of the tribal tradition, which is respected by lip servers on the one hand and sought to be destroyed on the other by planners and policy makers in the name of modernism. Sites which have been considered sacred by countless generations of tribals—their ancestral homes and burial grounds (Pathalgara, Sasan); Sacred Groves (Sarna) where the ancestor spirits dwell; their council and dance grounds (Akahara);the mountains revered as deities (Maran Buru); and the springs sacred to the memory of spirits (Chua)—are all facing destruction in the rapid process of “development.” The change of dress and language also threatens to erode the harmony of tribal life. Furthermore, their relationship with their environment, of which their wall art is but a natural expression, is in danger of disappearing due to the coal mines and industry that are appearing on tribal lands. Preserving wall art and ensuring the perennity of tribal heritage requires rejecting modernism, despite the fact that ironically their art also represents ‘primitivism’ which is the objective of modern art.

The simplicity of a carefully painted earthen floor or richly decorated Khovar rooms and walls, and its undeniable right to exist, must be defended at all costs. It is a human right and a heritage which unborn generations have the right to inherit. Today, the flowering of this delicate and primitive art form in the Hazaribagh jungles stands threatened. Yet this work, and others like it, are testimonies to the ancient people of pre-literate societies who carried the responsibility of cultural heritage and its artistic expression forward through oral traditions, indigenous knowledge, and rituals.

--------------------------------

References:

1. Imam, Bulu. 1995. Bridal caves: A search for the Adivasi Khovar tradition. New Delhi: INTACH.

2. Imam, B. and Majumdar, M. Hazaribagh: Traditional Wall Paintings of Jharkhand. Publication date to-be-determined.

Femmes du Hazaribagh is a not-for-profit association whose mission is to preserve the endangered tribal heritage of ritual wall paintings by providing financial support for material costs and compensations for the women artists. For those wishing to donate to their cause, please visit Femmes du Hazaribagh or contact the association at deidivonschaewen@yahoo.com

Bulu Imam is a cultural revivalist and an environmental activist working for the protection of tribal culture and heritage in Jharkhand. Since 1987, he has been the Convenor of INTACH Hazaribagh Chapter campaigning to save the upper Damodar Valley from coal mining. He has brought to light 14 new rock art sites in Jharkhand, and the Sohrai (harvest) murals painted on the walls of the mud houses of the Hazaribagh. He established the Sanskriti Museum & Art Gallery in Hazaribagh in 1995 along with Tribal Women Artists Cooperative (TWAC) and has promoted the tribal art of the region, holding over 50 international exhibitions of Sohrai and Khovar paintings in Australia, Europe, and the UK. He is the recipient of the Gandhi International Peace Award (2011, House of Lords in London) and the Padma Shri (2019). As an author, researcher, and an authority in archaeology, tribal and rock art, as well as vernacular folklore and history, he has written books and articles and has made several films on tribal art and the culture of Jharkhand.

Deidi Von Schaewen studied painting and graphic design at HDK Berlin. Photographer and filmmaker, she lives in Paris and travels the world. Eyes on the alert, she collects the neglected signs of an urban scenography, the “ready-mades” of the street, and has produced sequences (Walls in Berlin, 1961, Scaffoldings in Barcelona, 1965; Sidewalks of the World in Paris, 1977). Her other passions include the vernacular, the huts in Africa and Asia, and plants and trees (Sacred Trees of India). She has exhibited in international galleries and museums since 1974 and has also worked for many architects and designers. An avid journeyer, she has traveled the world for Taschen (Fantasy Worlds 1999, Interiors of India 2000, Inside Africa 2004), and for other publishers. Several books are in preparation and Wall Paintings of Hazaribagh is one of them. She is the founder of the association Femmes du Hazaribagh that helps woman painters of Hazaribagh to continue their art.

Minhazz Majumdar is a curator, writer and designer who is deeply involved in preserving and promoting traditional Indian arts and crafts. Majumdar has worked on groundbreaking shows on India in the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia and has built collections of Indian art for museums and collectors across the world.

EDITING: COPYRIGHT © MOOWON MAGAZINE /MONA KIM PROJECTS LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

PHOTOS & VIDEOS: COPYRIGHT © DEIDI VON SCHAEWEN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TEXT: COPYRIGHT © BULU IMAM, © MINHAZZ MAJUMDAR. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TO ACQUIRE USAGE RIGHTS, PLEASE CONTACT THE COPYRIGHT OWNERS OR CONTACT US at HELLO@MOOWON.COM