Ahara directly translates as “food” in many South Indian languages such as Kannada and Telugu. Food is an essential part of our daily lives, yet something that has been an inspiration for artists, designers and craftsmen for its multisensory aspects. Whether for ordinary or special occasions, food “is a vehicle for expressing friendship, for smoothing social interaction and for showing concern.”1 Weaving, like cooking and eating food, also symbolizes social relationships and has become a central part of many communities in India. Throughout history, cooking and weaving have been instrumental in creating a strong social experience.

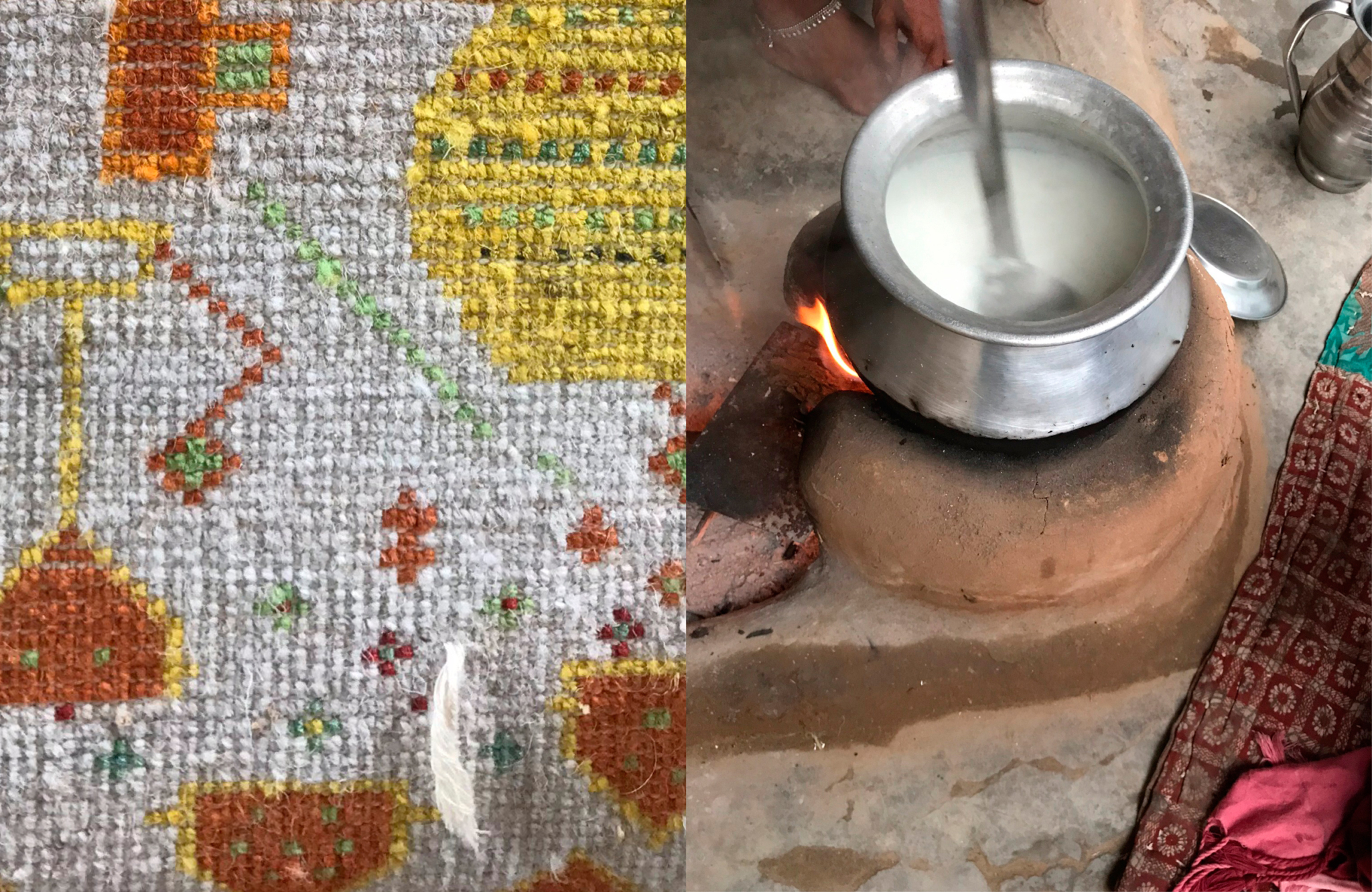

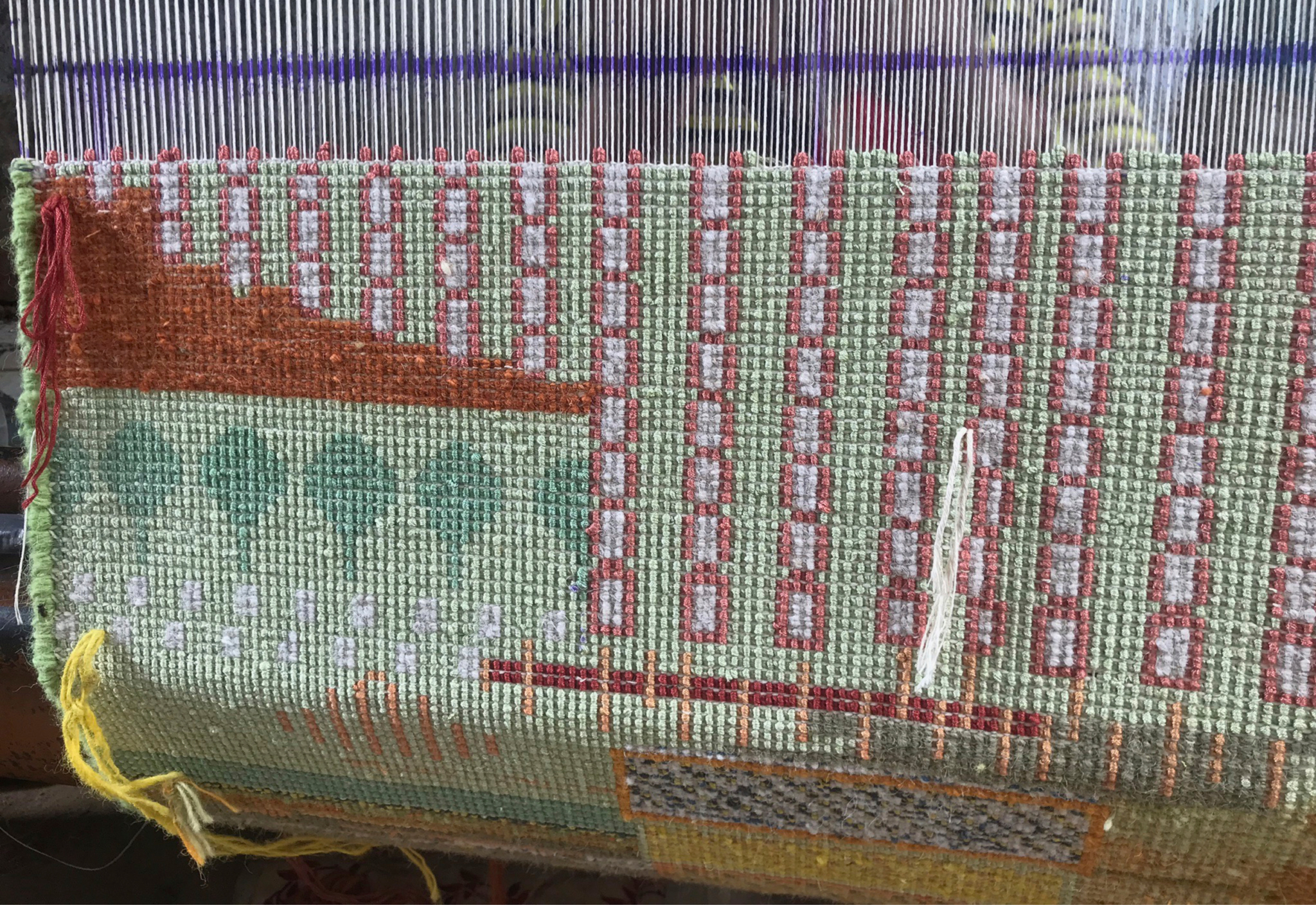

In Aspura, a village about 70 kilometers from Jaipur, cooking and carpet weaving skills which are mostly carried out by women, are important daily activities passed on from generation to generation. Both activities are opportunities for family members and the community to get together to share and exchange knowledge in the spirit of cooperation, support, and reciprocity. A large part of the day is spent discussing what meal to cook, how to prepare it, what ingredients are available and what needs to be bought. This is intertwined with thoughts and discussions on what yarn to use for weaving rugs, what needs to be ordered, what designs to create, and how to make it. Both activities “strongly affect the social relationships and act as a method of cultural exchange.”2 The Ahara project thus explored ways to creatively amalgamate the two activities that form an integral part of the community in Aspura.

through

Flavors, Colors, Motifs

Through the Jaipur Rugs Foundation that empowers rug weaving communities in India, 75 women artisans in Aspura weave rugs on a daily basis as a means to transform their lives and the lives of those around them. The youngest of them, 24-year old Bugli, has learned this craft from her mother who had learned it from her own mother. When Bugli’s father was alive, her mother wove rugs mainly for her own use, whether it be to give as gifts or as secondary income to her father’s seasonal earnings as an agriculturist. After her father passed away five years ago, Bugli learnt the craft from her mother so the family has constant earnings throughout the year.

Through the foundation’s initiative Manchaha, which literally means “from the heart”, weavers are given the freedom to weave, not on the basis of a mapped design as was the norm, but to create something of their own. With this in mind and with an aim to challenge the traditional design process where the designer directs the craftsmen to create a product, the Ahara project began as a co-design initiative. Its aim is to encourage empowerment through inclusivity and non-authoritative design principles, allowing artisans and designers to collaborate together from design conception to completion.

To enjoy the full story, become a Member.

Already a Member? Log in.

For $50/year,

+ Enjoy full-length members-only stories

+ Unlock all rare stories from the “Moowon Collection”

+ Support our cause in bringing meaningful purpose-driven stories

+ Contribute to those in need (part of your membership fee goes to charities)

Kshitija Mruthyunjaya is an architect, designer and artist. After completing her bachelor's degree in Architecture in Bangalore, India, she moved to the UK where she pursued an M.A. in Regeneration and Development and an M. Arch. (RIBA Part 2). She worked for a leading firm in Bath, for several years before moving to Milan to pursue her Masters in Design. Apart from architecture and design, her passions include research and writing. She collaborates with not-for-profit organizations and local artisans in India to keep traditional crafts alive and to support economically challenged communities. Her main goal is to use her skills and knowledge in design as a regenerative action to create conscious and inclusive communities.

Jaipur Rugs Foundation is an initiative established by NK Chaudhary in 2004. Its key mission is to serve as a social innovator to promote the causes of artisans by providing job opportunities and enabling economic independence among rural societies. It trains rural populations in rug weaving skills so that they may become home-based artisans. Today, it has a network of around 40,000 artisans spread across five states of India who work with dignity.

EDITING: COPYRIGHT © MOOWON MAGAZINE /MONA KIM PROJECTS LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

PHOTOS & TEXT: COPYRIGHT © KSHITIJA MRUTHYUNJAYA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TO ACQUIRE USAGE RIGHTS, PLEASE CONTACT US at HELLO@MOOWON.COM