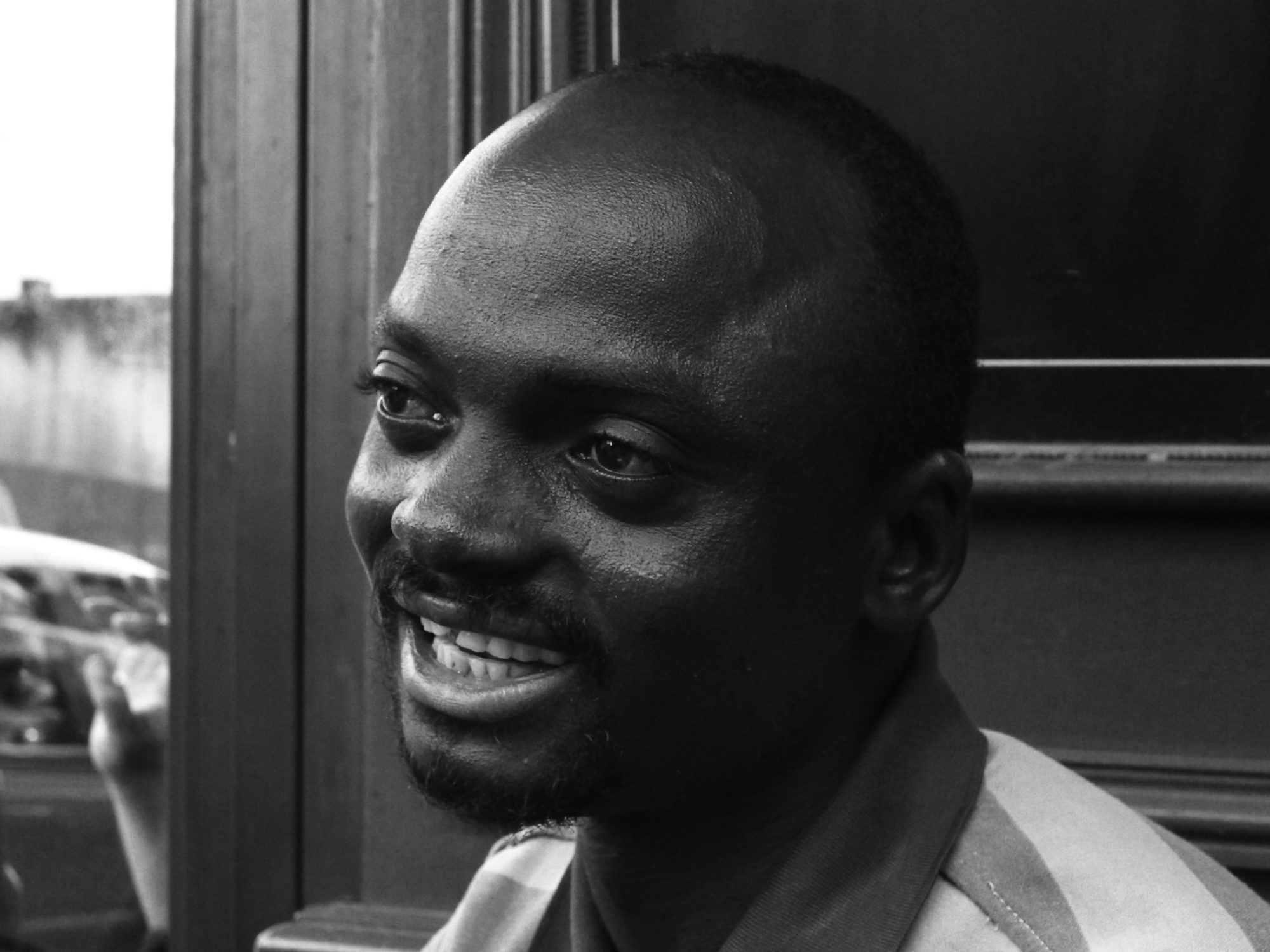

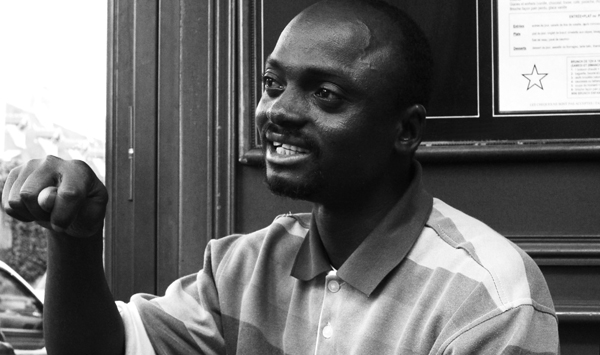

A sharp and determined man in his 30s, Emmanuel Ouoba is the very embodiment of charisma and optimism, qualities that stem from his earnest ambition for the success of his people. And this man is not afraid to break out the contagious Burkinabe smile at its 100% potential. Only then do we realize that most of us–especially those of us who live in "grey" Paris—often forget to engage that essential facial muscle at its fullest. Blame it on the lack of sun. The magnetic personality of Emmanuel, the contagious aspect of his entrepreneurial spirit, and his drive for a better world reminds us that weather is never an excuse to instigate change.

Emmanuel was the 2014 winner of Prix Artisan Entrepreneur, granted by the NGO Ethnik.org, to promote ambitious and innovative entrepreneurs in crafts. This brought him to Paris for a three-month study program at ENSCI-Les Ateliers in 2015 to see, absorb, exchange, and take it back home to push things in his homeland to another level.

Empowerment and independence of his people is at the heart of this man's mission, an ambition that has been a natural part of his being since his youth.

I understood early on in my life

that when you have a master,

you can never be independent.

Today, in the village of Manga, there is a center that trains women and youth with skills so that they can acquire employment and independence. Emmanuel founded REHOBOTH Training Center shortly after he married. Seeing his wife weave from time to time sparked the idea to train others in this skill, since the market was there and many of the women and youth in village were unemployed.

Hence, in 2007, while still a civil servant, Emmanuel opened the center which trains villagers to make clothing or pagne*, also called Faso Danfani** in local language. By 2013, the center was so successful that he left his position to dedicate himself fully to its activities, which included creating REHOBOTH DANFANI+, an enterprise dedicated to the production and commercialization of the products from REHOBOTH. This drastic move to relinquish the comforts of such a coveted position shocked people. But all along, he had a bigger dream.

"I did not enter civil service to make a career out of it. It was a point of departure that would allow me to pursue my own initiatives. I understood early on in my life that when you have a master, you can never be independent. But looking back, I made the right choice. Leaving and letting go of that sense of 'security' really opened me up so that I could forge my character and personality."

(*) Rectangular piece of cloth used as garment that wraps around the body

(**) Traditional textile and Burkina Faso's national cloth.

It is a hand-woven cotton cloth whose term was born during the time of revolution under Sankara's leadership.

It means "woven cloth of the homeland" in the Dioula language.

One cannot wait

and expect life to give him gifts.

One must strive for things.

That is how I see things.

When the center opened, it was initially based on the system of paid tuition. But they soon realized that there was a fundamental problem: many people did not have the monetary means. As a solution, the center trains those with a genuine willingness and desire to learn in exchange for their commitment to work at the center post-training, as a way to pay back the tuition expense. Some trainees set up independently after their time at the center and others decide to remain as paid hires.

This system fosters motivation—motivation to learn, motivation to work for one's livelihood—which are traits connected to independence. This brilliant management thinking encourages long-term solution. "Weaving is an activity with many constraints; it is a test of one's patience and will. Without these qualities, one won't last. For example, there are those who are able to afford the tuition, but they eventually quit because they realize that weaving is not easy as they had initially thought."

It is a philosophy to which he strongly adheres. Emmanuel believes that giving people something free could hinder their understanding of importance of things and cultivating their sense of work ethics. "This sense of responsibility that we try to foster in the center applies and translates to life in general. One cannot wait and expect life to give him gifts. One must strive for things. That is how I see it."

Trainees at REHOBOTH Training Center in the village of Manga, Burkina Faso.

Emmanuel contributed to his school tuition from the early age of 10. "Because there were six kids in my family, it wasn't easy for us. During the rainy seasons, after finishing working in my dad's field, I continued on to other people's fields in order to earn money for my brothers and sisters' school materials. As the eldest, I wanted to help my mom pay for our tuitions. My dad never knew about this because in our village, this is normally the women's responsibility and it is unusual to see men (especially those who are not educated) pay for school fees."

This personal work culture and ambition continued throughout his life, at times appearing in comical counter-culture situations. "Here is an anecdote to demonstrate to what degree our men discharge all responsibilities to women. Before dyeing, one must wash. So you can imagine, for a man—let alone a civil servant—in the context of Burkina to be seen 'washing' is quite a rare sighting. After work and during the weekend, I would dye the thread that would be used for weaving during the week. A man washing and dyeing, a man who does women's work…this turned people's heads in my village! One day there was an old man who was passing by while I was washing. He said to me, 'My son, is your wife ill, that you are washing your own clothes?' And I replied, 'No, she is not sick. I just like to help her, that's all.' This man shook his head and continued on his way. Perhaps he was thinking to himself that this young man is foolish."

A Faso Danfani from REHOBOTH Training Center

Sankara's desire to create a more equitable existence for the people of Burkina Faso is still very much alive and kicking in entrepreneurs like Emmanuel who continue to work to make this a reality . However, the politics of natural resources remain an unresolved issue. There are many Burkinabé who weave and are involved in textiles. Yet there is only one factory that produces thread in Burkina—and one factory cannot supply the high demand.

The main problem lies in the fact that the majority of their cotton is exported as raw material, which prevents the locals from transforming it, partaking in the production process, and reaping benefits from the added value this brings. Instead, all this is done outside of the country. In addition, raw materials are sold at such a low price that it becomes a form of exploitation by importing countries.

"In that sense, we are robbed of our own natural resource. In essence, we are a country of 'consumers' because most of our natural resources go elsewhere at a low price. And since we do not transform these resources, there is less added value and employment for our people." Unlike other global economies that reap benefits from the development of an industry, the country remains poor because it is unable to develop by working its own natural resources and creating employment in the process.

This is a far cry from Sankara's time, when the leader instated a rule that obligated everyone to wear the Faso Danfani—even the military. During the period of revolutions, there are rules that are set in place and things are never quite democratic. But Sankara's vision was to influence the people to consume locally made products in order to stimulate the economy and create the cycle of employment internally. At the same time, he wanted to encourage egalitarianism by eliminating the disparity in social standing that is visible through clothing.

Everything that one does in life

should be done in excellence

and with perfection.

As the recipient of Prix Artisan Entrepreneur award, Emmanuel encountered Paris for the first time in his life. During his three-month stay, he studied at the prestigious ENSCI-Les Ateliers with students from all over the world. But it was the city itself that was the most profound experience for him.

"What I learned was eye-opening. I learned an enormous amount by being in Paris, by walking its streets, by visiting museums. It confirmed that I needed to push my pursuits to their utmost possibilities. Here, everything is done with rigor and quality. Everything that one does in life should be done in excellence and with perfection. When you are in the midst of a creative process in a new cultural setting, you start to see details that others do not see. The trees, even the fencings around the trees, are a work of art! I've never seen that done in that fashion. Then there are the colors! There is a language behind colors here. Attributing mood, emotions, and seasonal usage for colors—all of this was new to me. It certainly shaped the way I see things. In Africa, we are all about a splash of colors without giving them much reflection. It was a process that helped me to better understand the European market and its intricacies."

Then there is that marvelous yet universally comic education of being in another culture and encountering "the other." "When I arrived here, I didn't understand. I would enter into the metro and as it is natural for me, I would say 'Bonjour'. People just looked at me as if I were a crazy man. Of course! We don't know each other! Back home, we are not accustomed to this lack of trust that is common in big cities like Paris. When we are on the street, we exchange hellos whether or not we know each other. So that was a bit of a culture shock for me."

In Emmanuel's eyes, each and every person is born to occupy a place in his or her community. And if one does not occupy it—and occupies it well—no one else will. He believes that what is in one's control is the way one shapes his or her fate, regardless of the situation or condition to which one is born.

"I was born into a condition, I grew up in a condition, and I know what poverty is. I know it well, because I lived in it. I also know what it feels like to have a decent life. So I know both. So what I can bring, especially to the youth of my community who are not yet conscious of this difference, is to awaken them and cultivate their sense of responsibility to strive for things. I wish to be a role model to incite hope for my people and to awaken their awareness to the fact that no one is there to save you. That needs to be your own initiative."

So, should we nominate Emmanuel Ouoba for TED talk?

Emmanuel Ouoba is the promoter behind REHOBOTH Training Center based in Manga, Burkina Faso. The center trains women and youth in the skills of dyeing, weaving, and sewing to prepare them for a career in textiles. He is also the director of Enterprise REHOBOTH DANFANI + that specializes in the production, processing and marketing of apparel made from artisanal textiles. Emmanuel also manages Association for the Development and Integration of Rural Youth (ADIJR), whose objectives include socio-cultural and economic exchange, community development through social mobilization, and mobilization of youth. Designer, weaver, and dyer, Emmanuel holds certificates in natural dyeing from MOGARE center of Ouagadougou and in two-pedal weaving from FANIMA Center of Fada N'Gourma. He has participated in several exhibitions at both the national and regional levels. In 2014, he was the winner of Prix Artisan Entrepreneur organized by the NGO Ethnik.org.