We live in a time of paradox and opportunity. Sustainable production and consumption is claiming their space against the backdrop of climate change. Sensitivity to renewed history and heritage is growing in parallel with the profusion of automation and artificial intelligence. Savoir-faire, in the form of rich and fascinating documentation on handcraft techniques and processes, is more accessible than ever. In this context, we are witnessing a growing interest in artisanship and the notion of the handmade at a mass level.

Yet, we seldom hear about the process of people who collaborate creatively with artisans to forge possible links and to inspire values we may all learn from. They are important actors who can make an impact in local communities, in the market by the nature of objects we consume, and even in our environment.

These magical behind-the-scenes figures are the cornerstones of sustainable and evolutionary artisanship. They are both a catalyst and a "bridge" for the artisan communities with whom they collaborates.

Nelson Sepulveda, a prolific Paris-based creator of Chilean origin, has been working for years with artisan communities in countries across the world: Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia, Guatemala, Colombia, China, Indonesia, Swaziland, South Africa, Philippines, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, and Mexico. He has heartfelt concern for the welfare of the artisan communities with whom he collaborates, and cares deeply about the positive impact one can make. His "small contribution," as he puts it, has something to do with the process of collaboration that involves connecting, linking, renewing, and reclaiming.

Photo: Mona Kim

Photo: Mona Kim

Photo: Mona Kim

Photo: Mona Kim

Dried seaweed fragments

foraged from the coast of Chile cork the glass bottles.

They resemble chess pieces created from nature.

Unruly fern leaves and Jurassic-size dandelions seed heads

sprawl wildly out from a vase.

Thick rings from Ethiopia, Germany, and Spain

are deeply immersed in royal slumber inside a glass jar.

Feathers inside images

and feathers on a dream catcher sculpture

protect the salon from spirits.

Loose groupings of books, sketches, and exquisite images

hint at organic order.

Photo: Mona Kim

Photo: Mona Kim

Photo: Mona Kim

Photo: Mona Kim

Upon entering, a voice emerges from the kitchen, as if one had stepped right in the midst of a conversation that had started long before. The soft clatter of wood, ceramic, and other earthy materials can be heard as simple ingredients and spices are being carefully concocted. One also senses that colors, shapes, textures, and multiple images are being connected simultaneously in his mind ––in real time.

Nelson is like a nomad one may imagine encountering in a solitary mountain path in the deep Andes. The texture of his person evokes trees, leaves, shells, and natural elements from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. He is an ancient soul with unruly hair who may have been napping under a tree, rummaging for pieces of leaves, or intensely observing a stone he had found. Yet, oddly, he is in constant flux.

Photo: Mona Kim

From Bloom issue 14 (left) and 6 (right).

Concept and styling: Nelson Sepulveda.

Photo: Thomas Straub.

From Bloom issue 4.

Concept and styling: Nelson Sepulveda.

Photo: Michael Baumgarten.

His home is an unbridled museum full of mysterious objects and images that conjure up faraway places and the rich tapestry of life. It is a repository where fragments of culture from around the world, the earthy textures of nature, and some of the most beautiful creations and images dwell—all strongly connected to his life journey, his work with the artisans, and his work as a driving force behind the lush, earthy, and highly-sensorial images from the early issues of Trend Union's Bloom magazine.

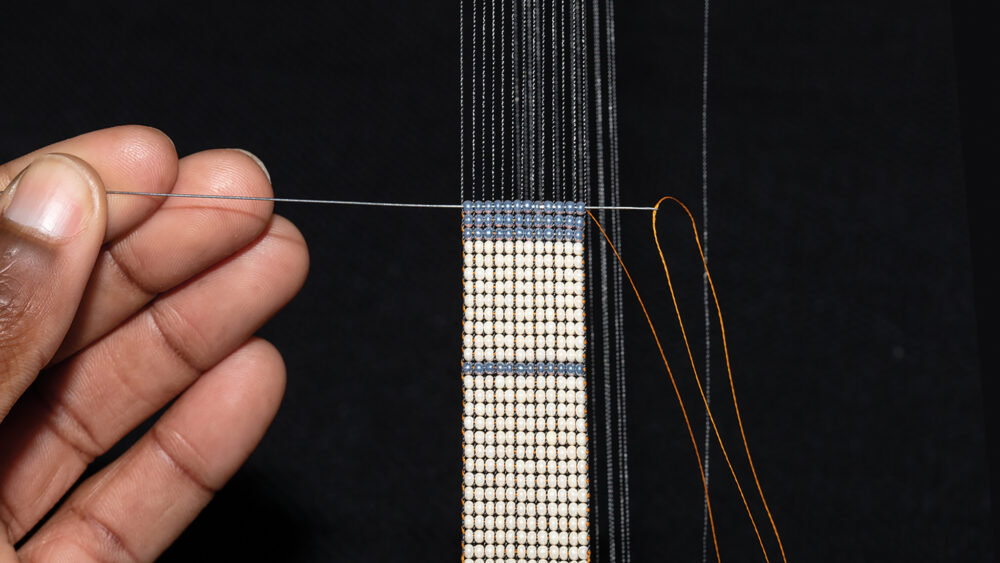

Nelson's sensibility for simple natural materials, handmade work, and "rummaging," an inherent process in his work with artisans, took root during his childhood. Growing up in the countryside near Santiago in Chile, he was exposed to potters, woodworkers, and various artisans who worked with humble materials they found in their surroundings be it mud, grass or discarded materials. In place of store-bought toys, he embraced nature at an early age as his main material source for play and creation. He connects this back to his mother. "As an adolescent, on every little trip, I was always interested in places where artisans were. I loved to watch old ladies making handspun thread. A week or month later, all the materials they were preparing by hand were already on the loom and they were weaving. I found that so extraordinary. All these things nourished me."

With most artisans,

it's important first of all to put energy into building a

confident relationship and a real collaboration,

where he and I become extensions of each other,

like a bridge.

Nelson's first experience working with China was during its early days of technology and computers. He wanted to explore the use of bamboo as a weaving material. "It was funny because when I met the Chinese team, everyone introduced themselves to me as an engineer, architect, etc. They asked me who I was and I just replied, 'I'm Nelson'." He brought a shoebox containing a tiny nest to share with the team. "This is what I'd love to work around." Everyone thought he was a bit nuts.

Following his unconventional entrance to this first project in China, the magic of connection and collaboration unfolded. As a way to communicate with the artisans, he started to weave with his hands. One came and sat next to him then another came, culminating in an entire circle of people all weaving together. At some point, they were completely synchronized in their breathing and in their rhythm of weaving. "It was incredible. It was almost like a ritual."

Sometimes he would bring a watermelon or pomegranate from the market as references for the form he wanted them to understand. Or, he would redraw the shapes that would help them to make the jump to immediately start blowing glass, for example. For Nelson, constantly inventing ways to communicate on the spot, using locally available references, creates synergy and brings them one step closer to working together. "It's so beautiful because you see them doing incredible, beautiful things. I simply need to be attentive and follow every movement." Sometimes he interrupts the process, when a beautiful accident occurs; he tries to capture it and reproduce it. Such powerful moments of collective discovery brings magical energy and impassioned drive for everyone. "Then people start to propose things. And I love when that happens because it means that the connection has been established and that they are interested and fully implicated."

He considers these processes, which he calls "reconstruction of the collaboration," an essential part of the project. "It is not about arriving somewhere and saying 'Ok guys, this is what you're going to do. And I'm going to be back in six months, so just try to produce these things as drawn." For Nelson, it is about having faith in the now of the process and working together toward the unknown, a discovery. For this to be possible, being present and cooperating together throughout the entire process is key. "I never had to push the artisans that this is what they have to do or completely ignore what they're able to do. It's important to have that sensitivity."

Photo: Nelson Sepulveda

I like to show artisans what has

always been there and try to instill in them a sense

of deep value for what is in their surrounding

and the legacy of their culture, instead of looking outside

and reproducing what's coming from elsewhere.

Working with local materials differently to find something new to tell has been the main thread of Nelson's approach since his first experiment in Indonesia. Recently, he has been driving a project for a government-sponsored initiative with 16 diverse workshops situated in Philippine's villages. To create a link between the artisans and their context, he has been collaborating with them to co-develop techniques that evolve around natural materials found in their immediate environment: for example, paper for lamps made from natural wastes such as banana leaves, pineapple, and corn; cords for rugs made from abacá (fiber from banana tree trunk); and rigid material for weaving such as buri (palm).

Photos: Nelson Sepulveda

Photos: Nelson Sepulveda

"When I arrived in the Philippines, I realized that there was an abundance of beautiful, incredible materials growing there by themselves. They just grow. Nature is very generous with them. Yet, in these places, the people often lose connection with these things."

Upon arriving at a place, the first thing that Nelson instinctively does is to scan. He seeks out what is immediately visible in the environment, rummages through what the ateliers consider to be trash, touches, analyzes, "shakes the dust off," and enquires where a certain natural material came from. "I never try to push the local artisans to make things with materials that will be difficult to harvest, difficult to find, or have to be imported from far away places." He is convinced that eliminating such impediments and making things easier for the locals encourages them to pull from their surroundings, refocus on local resources, and reclaim what has always been right under their nose.

Photo: Nelson Sepulveda

One day I told Farouk he should stop smoking.

He just laughed and told me that he started smoking

since 12 years old. So, if he suddenly stopped smoking now,

he'll probably die.

One often has the expectation that artisans should use the materials and skills they possess to execute on a "recipe." For Nelson, it is important to take the step to understand the material and what the artisans are doing with it before new ideas can transpire. Sometimes, he takes hours to simply observe their rhythm in order to understand. Even a slight change in their rhythm or in their physical position can trigger something new and bring refreshing surprises. These intentional "disruptions" are introduced after Nelson has made efforts to learn the basis of the artisans' crafts, without the pretending to acquire or copy the ease and the beauty of their art which took a lifetime to master. "When I try that same technique with my own hands, the exercise itself brings something that transcends mere understanding. It is hard to describe."

One of his deepest impressions and cherished connections occurred in Cairo's City of the Dead in Egypt. When he arrived at a potter's cooperative, they designated one sole artisan with whom he could work. He was an old man, all the way at the back of a big room, who was making identical ashtrays over and over again. "I said to myself, 'an old man like him must be the real treasure.' So I just sat with him, observing him for hours. Farouk had a fantastic control of what he was doing without even looking. For me, that meant he possessed a very high level of his craft."

When they both reconvened next morning, Nelson placed drawings and photos in a circle, just to see how Farouk would translate these without explicit visual directives. Visual references that Nelson shares with artisans are often drawn from historical references or elements in their immediate surrounding, those they can recognize and connect with. In Egypt, he referenced shapes and textures of bread being transported on a monumental head basket in the streets; the tones of the local milk; and the colors of the Nile. This is also a way for Nelson to mold himself to their surroundings in order to find mutual points of connections.

Once the connection is created, Nelson starts to "play," searching for the new in the old. One day, he asked Farouk to try something asymmetrical at the potter's wheel by encouraging him to experiment with found "tools" such as a stone or a branch. "That 86-year-old man was having so much fun that he turned into a little child. That whole exercise was fantastic." Farouk then generously transmitted this technique to a young boy from his neighborhood who had a gift for handcraft. This boy, in turn, had someone create tools that cloned the forms of the found objects. Basically, they had integrated this new method and created entirely new tools.

Photo: Nelson Sepulveda

People who are in the so-called

'creative marketing' often bring their ideas to places,

without consideration for identity, history, and context.

I like to hope that each cultural group could create a 'brand'

that is proprietary to their culture.

For Nelson, artisan communities that produce things without a soul or that are disconnected from their context is a damaging reality in the world today. Often, governmental organizations whose initial objective was to create work for communities using local skills, engage middlemen who buy their products for foreign export. Rather than having a direct dialogue with the artisans who hold the skills, they rely on the middlemen's insight on what the market dictates. Consequently, this dictates what artisans have to make, turning them into mere mechanics. This causes a loss of confidence and a sense of identity, as well as more meaningful and deeper engagement.

Nelson is a counterforce to this trend. As a proponent of exporting cultural identity instead of importing cultural identity for the sake of competing in the international market (reclaiming versus re-appropriating), he focuses his energy on helping communities to understand, see, and align themselves to the big picture—that's to say to build a new foundation for their crafts, target new markets, and nurture identity that is authentic and proprietary to their culture. In order to establish credibility, he accentuates the importance of being consistent, stable, and steadfast in what they are creating instead of being directionless or responding to ephemeral market trends. "In Philippines, for example, we want to attract people again to raw beauty. But in order to do so, we need to focus on unique objects instead of the mass-produced. In tandem, it involves helping them develop sensitivity and consciousness toward how certain natural materials lend themselves to certain structures or objects. I wanted to prove to them that they can all raise the bar of quality much higher, attract a higher-level market that has stronger sensitivity for sustainability, and appreciate the notion of bringing nature inside their homes."

Photos: Nelson Sepulveda

Nelson Sepulveda is a creator of artisan-made homeware, furniture, and objects. He travels the world to collaborate with local artisan communities for collections he develops for the brands Ay Illuminate and Cinq Etoiles. During his early days in Paris, Nelson designed makeup ranges for luxury brands. He later joined Edelkoort Studio, where he provided creative direction for View and Bloom magazines. He has been a contributing art director, set designer, stylist, and editor for various editorials including Mairie Claire, Selvedge, Le Monde d'Hermes, and Architectural Digest. He has also collaborated on special projects for the brand Dosa. Nelson is represented in Paris by Gallois Montbrun & Fabiani Agency.

Mona Kim is the Founder and Curator of Moowon magazine. As the Creative Director of award-winning multidisciplinary design studio, Mona Kim Projects, she has been conceiving public space experiences and large-scale experiential projects for global brands and cultural institutions. Her museum and exhibition design for the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, World Expo, Museum of Tomorrow (Museu do Amanhã), and UNESCO-sponsored projects, gave her the opportunity to document and be exposed to some of the most distinctive examples of social realities and cultural expressions. On these projects, she had co-curated world issues such as endangered languages, cultural diversity and sustainability. The Moowon project is an extension of this background. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, WWD(Women's Wear Daily), The Creative Review, and in publications by Gestalten and The Art Institute of Chicago.