East Africa and the Indian Ocean is a region of the planet with its own set of maritime knowledge, overland travel methods, customs, languages, cultures and religions. For thousands of years, trading ports and desert market cities have dotted this region. These were places where merchants, traders, pilgrims and explorers could find shelter, rest, eat, buy and sell goods. Lying just west of the Somali coast and south of the Red Sea in a part of the Bilad al-Barbar, a term given by medieval Arab geographers referring to the northern part of Horn of Africa, is the ancient land of Abyssinia. Today, we know this land as Ethiopia.

The name Ethiopia often brings to mind certain images. However one may imagine it, it is not a land of one people, one language, one religion or one type of landscape. It is an ancient country made up of many different peoples, cultures, religions and landscapes.

The focus of this work is on the dry, desert-like eastern side of the country which borders on Somalia. It is an area that has long been connected in culture and trade to Somalia, the Arabian Peninsula, the Red Sea and the nearby Indian Ocean coastline. It is also an area, by the nature of its location, that has forged a strong Islamic presence over the last millennium. Mecca in Saudi Arabia, the birthplace of Islam, is not far; and with just a short boat passage over the Red Sea or the Gulf of Aden, the entire Semitic world, with its religions and languages, was able to mix easily into the native cultures of the Horn of Africa.

The cities of Harar, Dire Dawa, Jijiga are remnants in a region of what was once the Sultanate of Ifat. It originated in the 13th century and stretched from the shores of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden into the dry interior of Eastern Abyssinia. Harar, dating back about 1100 years, is the oldest city of the group and is reminiscent of the planet Tatooine in Stars Wars. These desert cities are known as Islamic Centers because they have specific aesthetic and religious features of the Orient. The Orient, in traditional historical terminology, refers to the East or that of the Eastern World which includes both the Near East (the Middle East) and the Far East (Asia).

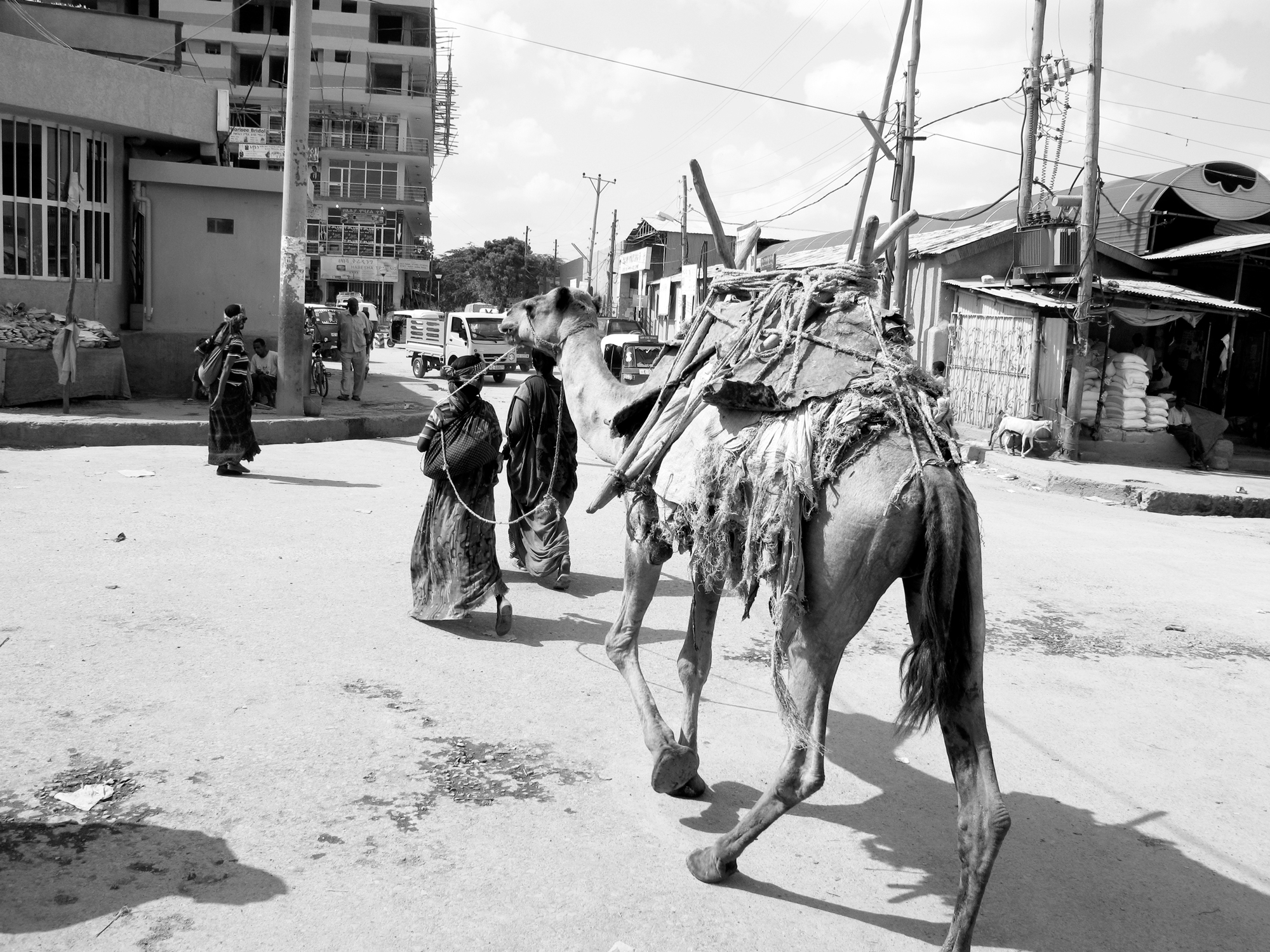

The Horn of Africa has long been known for its many different caravan routes which transverse its interior and hills, as well as merchants' use of camel caravans as a method for transporting goods across land. It is also known as a major producer of myrrh (mur in Arabic), particularly in the east of Ethiopia and in Somalia. For the past 3000 years, the stories and legends that speak of the interconnectedness of East Africa, the Red Sea and the Arabian Peninsula have been virtually incessant. These include tales of caravans, laden with riches and incense, crossing the dry landscape and arriving to King Solomon's court in Jerusalem (1000 BC); the Queen of Sheba and her relations to the Kingdom of Judah and Israel; the Three Wise Men and their visit to baby Jesus; and the legends of Ophir and Tarshish.

The riches of the South (the South denoting the Arabian Peninsula and Africa in relation to the Mediterranean and Kingdom of Israel) seem to be a constant theme in many of these stories. Gold. Frankincense. Myrrh. Ivory. Sandalwood. Cinnamon. Riches of another era, these substances were so revered and valued that legends were born around these and their transport. The Queen of Sheba, ruler of Yemen, Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan and Egypt, brought gifts of jewels, frankincense and myrrh on the backs of Camels to King Solomon's court. It is said she left months later with a child inside her and several Israelites to accompany her on her long homeward journey. This was believed to have been the origin of the Falashas, Ethiopians of Jewish faith.

The Three Wise men, or magi, a tale as popular as any among Christians worldwide, are said in some accounts to be Caspar of Tarsus, who brought with him gold for the infant Jesus; Melchior from Arabia, who brought frankincense from his native region; and Balthazar of Saba (Yemen and Abyssinia), who brought myrrh which was native to his region. Other historical accounts claim them to be Gaspar the King of India, Melchior the King of Persia, and Balthazar the King of Arabia.

The stories of Ophir and Tarshish also connect back to Solomon the wise King of Israel. It was said that every few years ships, which he had sent out, would return back to Israel in both her southern Red Sea ports (near present day Eilat) and her Mediterranean ports (near present day Gaza) yielding riches from faraway lands. Tarshish, believed to be somewhere in the northern Mediterranean and possibly in Spain or Turkey, produced boatloads of precious metals such as silver, iron and tin. Ophir, which is believed to be either Africa and its East Coast or possibly India, produced boatloads of gold, ivory, sandalwood, pearls and other spices such as black pepper and cinnamon.

Ideas and images of the desert and the Orient have fascinated the Western mind for centuries. North Africa, Northeast Africa and the Arabian Peninsula have long represented a vast, impenetrable and harsh land. Lines of slow-moving camels with their turbaned masters bringing wonders and riches from afar, beautiful women secluded and kept from sight in harems, the insightful tales of Arabian Nights: One Thousand and One Nights, the Orientalist painting movement, are all parts of the fascination and mystique which has built up over time around the desert and its inhabitants. Why such fascination and mystique? A response I can propose is that this may have to do with the dress, the customs and the beliefs of the Orient that so strongly contrasts what the West regards as its own norms. Often such stark differences between world cultures seems to be the spark which has enkindled the intricate and perennial tales that have come forth from our captivated imagination. And then there is the curiosity which arises when one cannot view something fully: the female face behind the veil; the male face and head under the many layers of twisted fabric turban; the numerous women unseen behind the harem walls; the voice which creates the azaan or call to prayer at the mosque.

Why am I here?

The desert, the solitude, the silence, the markets, and myrrh.

My own explorations through the many markets I found during my trips to Ethiopia brought me literally face-to-face with what I was searching for: grunting camels, hot dusty days, women with tattooed foreheads and cheeks, long quiet hours sipping coffee or sweet tea in the shade of a small café, and large sacks filled with the dried tree resin from the Commiphora Myrrha tree. Myrrh is known by many names in different dialects and languages, with the Arabic mur and Aramaic murr perhaps being the most ancient. Although its colors can range from light yellow to orange to dark brown or even black, it is its smell that is used to correctly identify it.

Myrrh is the traditional medicine of the desert. Rich in compounds called sesquiterpenes and terpenoids, it has the ability to heal a variety of physical ailments. It is a desert cure-all that has been used for coughs, rheumatism, open skin wounds and sores, gum problems, toothaches, dry and cracked skin, skin rejuvenation, and cancer. It has also been used over the past 5000 years as a natural perfume and incense.

As a sacred substance, myrrh's importance in this region of the world is unquestionable. The methods of preparation may vary, but local healers and doctors use myrrh in the traditional ways that were passed down to them in oral and written instructions. As it only grows in this small region (Yemen, Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia) in limited quantities, the value of this tree resin is very high. With the Western world's growing knowledge of natural medicines, myrrh has also been climbing to its top rung of important herbs for its many uses, its potency, and its health benefits.

East Africa is an incredibly exotic and wild place, where throughout time the cultures of Black Africa, the Arabian Gulf Coast, Persia and India all have melted together in some way. What I have found to be most interesting is that many things that are considered traditional desert elements still exist here and are in use in the same form they were thousands of years ago. Camels are still used to transport things; flatbreads, like malawa, are served with local honey for breakfast; markets offer the same goods and spices; and the trade of healing tree resins such as myrrh and frankincense continues even today. It's perennial and as breathtaking as your imagination allows you to picture it.

Wayne Bregulla is a Stockholm-based photographer and painter. He has an affinity for black and white photography, abstract painting and metal work. Wayne is also the owner and creator of Ramakrishna Designs, a small design company selling ethnic jewelry, rare gems and rocks from around the world. He majored in Cultural Studies and Comparative Religion at New York University and took courses in painting and illustration at the School of Visual Arts. "In short, my work is about what I find to be beautiful in this world. Myths, dreams, visions, the element of water and the color black are all of strong interest to me and how I relate to my work." Wayne's attraction to Ethiopia and Somalia has much to do with his deep interest in old trade routes and centers of cultural mixing. This has been the subject of several of his recent projects.