In Ojibwe language, Gaa-waabaabiganikaag,

or White Earth, means "where there is an abundance of white clay".

When one digs deep, one finds "white clay", which in reality resembles light grey.

This clay is used for pottery by local artists.

Dana Goodwin – Ojibwe artist and powwow dancer.

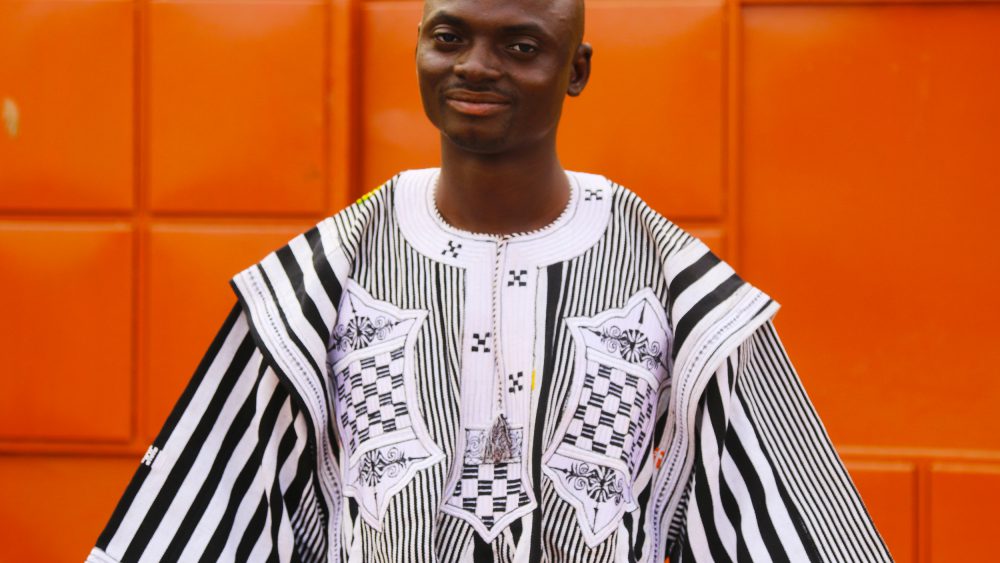

Dennis Williams - Grass dancer & beadwork artist.

They had a bumpy journey until they met 16 years ago and walked the path to sobriety in unison. Their deep love and tremendous respect for each other is very much palpable when she acknowledges they are able to learn from each other or when he emphasizes the perfection of her custom-made regalia. Dennis Williams and Dana Goodwin both work with children within their community and devote all their spare time to making regalia for family members or addressing custom orders. He's a beader and an accomplished Grass dancer while she's a fiber artist and an experienced Jingle Dress and Traditional dancer, like her mother and grandmother before her.

They made their home in Mahnomen(*) County on the White Earth Reservation in northwestern Minnesota to raise their twin daughters and the four children they've had from previous relationships. Living a healthy life, attending powwows, reconnecting with their Native language and educating children reflect the couple's holistic approach to the revitalization of their Native American culture, which has suffered decades of federal assimilation policies.

In the 1880s, off-reservation boarding schools were established to assimilate Native people into the mainstream of American culture. Children were taken away from their reservations and sent off to Indian boarding schools run like military institutions, where they would learn English, be strictly forbidden to speak their Native language and be raised as whites. Under the Assimilation through Education program, many generations of Native American children were brutally separated from their families and made to forget their language. In 1883, The Court of Indian Offenses outlawed Native American traditional ceremonies, claiming these rituals encouraged warlike passions among the tribes. This law would not be repealed until 1978(**).

Drawing strength from their Native spiritual beliefs that permeate into every part of life, Dana and Dennis have embarked on a soothing journey and their quiet determination cannot be derailed: "Without our own language we do not have that connection with our spirituality, but we also lose that identity that makes us different from non-Native people," says Dana Goodwin. By creating regalia for powwow ceremonies Dennis and Dana's are able to embody their commitment to the Ojibwe ways. Powwow dancing is a way to honor the mind and body, and dancers must stay fit and healthy for the contests. The traditional dances are also a way to honor and connect with ancestors, bringing a sense of unity for the family.

Objibwe: The Native word is "Anishinaabe"

(*) the Ojibwe word for "Wild Rice"

(**) 1978 – The American Indian Religious Act signed into law by President Carter

To enjoy the full story, become a Member.

Already a Member? Log in.

For $50/year,

+ Enjoy full-length members-only stories

+ Unlock all rare stories from the “Moowon Collection”

+ Support our cause in bringing meaningful purpose-driven stories

+ Contribute to those in need (part of your membership fee goes to charities)

EDITING: COPYRIGHT © MOOWON MAGAZINE / MONA KIM PROJECTS LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

PHOTOS & TEXT: COPYRIGHT © ANNE LAURE CAMILLERI. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TO ACQUIRE USAGE RIGHTS, PLEASE CONTACT US at HELLO@MOOWON.COM