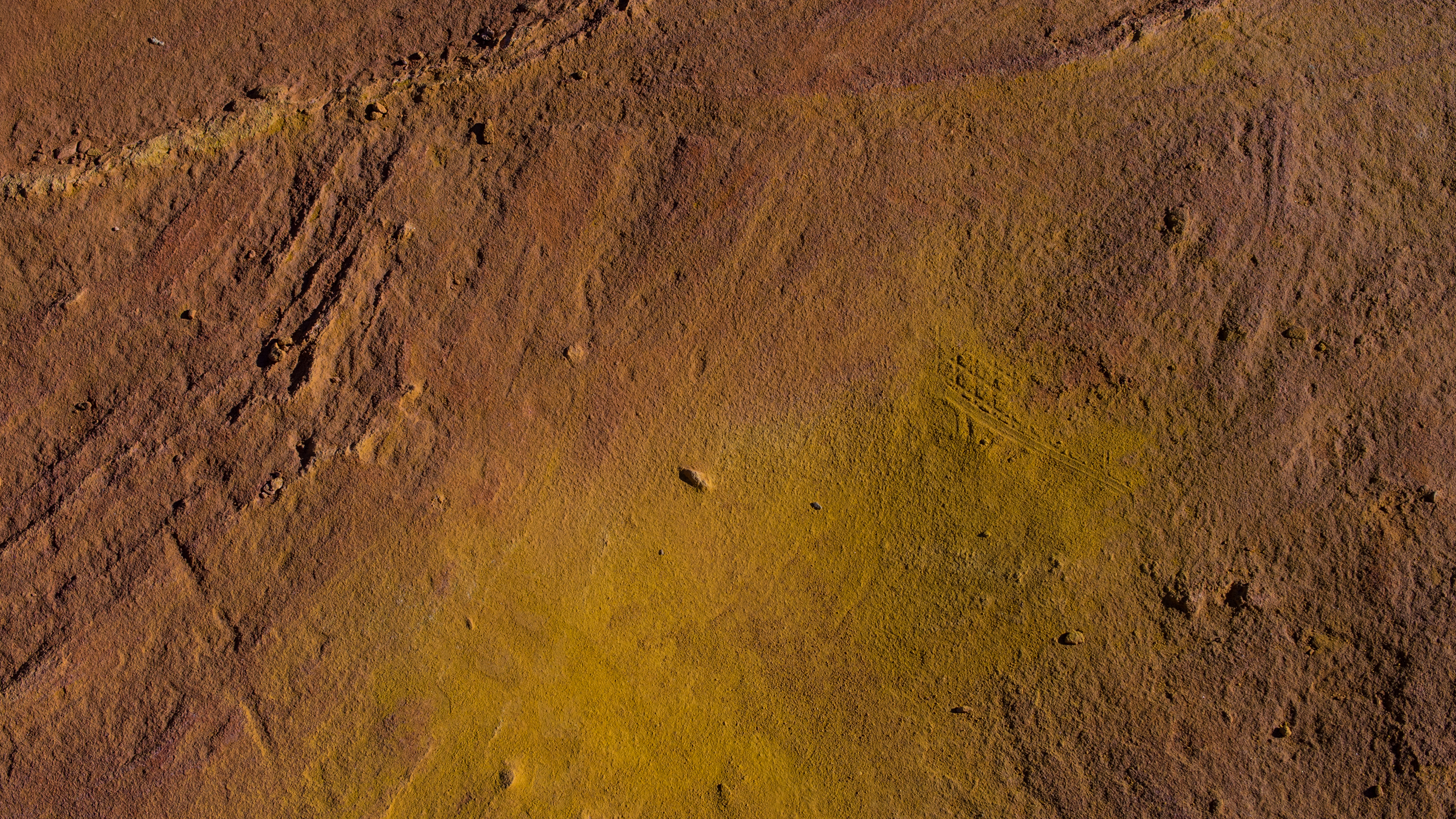

Though Italy, Australia, India, and some parts of North Africa are all sources of ochre, Provence is the largest in Europe and one of the largest in the world today. Its scale is about 25 kilometers long, 10 kilometers wide, and 150 meters deep, making Roussillon in Provence, France, an important source of ochre pigment since the 18th century. Today, Provence produces seven gradations of ochre.

Around 230 million years ago, Provence was under the sea. Roughly 117 million years later, an iron-laden clay mineral named glauconite—a result of a complex chemical process—formed green sandstone. As the sea started to move away and the tropical climate brought rain, sun, and heat, the change in chemical property of the green sandstone was triggered, and it transformed to a white clay named kaolinite. With iron oxide, it changed colors to ochre. Ninety-two million years ago the process of transformation had stabilized. The origin of ochre was discovered by a French geologist only 40 years ago. The presence of fossil shells is proof of the presence of the sea millions of years ago.

Today, in the Roussillon area of Provence, entire villages are bathed in this magnificent color from the earth. Its streets are a testament to a long history of man working in harmony with nature. These magical places seem to have sprouted out of the heart of one of the biggest ochre deposits in the world.

In the 1990s, a concerted effort to preserve and transmit a millennium-old knowledge was instigated. Ôkhra, Conservatory of Ochres and Color, was founded by Mathieu and Barbara Barrois. Installed in the converted industrial site of a former ochre factory in Roussillon, the Conservatory has become a center for education, training, and the transmission of savoir-faire of ochre and the materials of color.

Built in 1921, the factory was revived to tell the story of traditional processes that span from the extraction of color from inside of the mountains, to the color that breathes life into our objects, creations, and habitats.