"If the success of a civilisation is measured by its endurance over time,

then the San are by far the most successful civilisation in the history of modern Homo sapiens."

– Dr. James Suzman

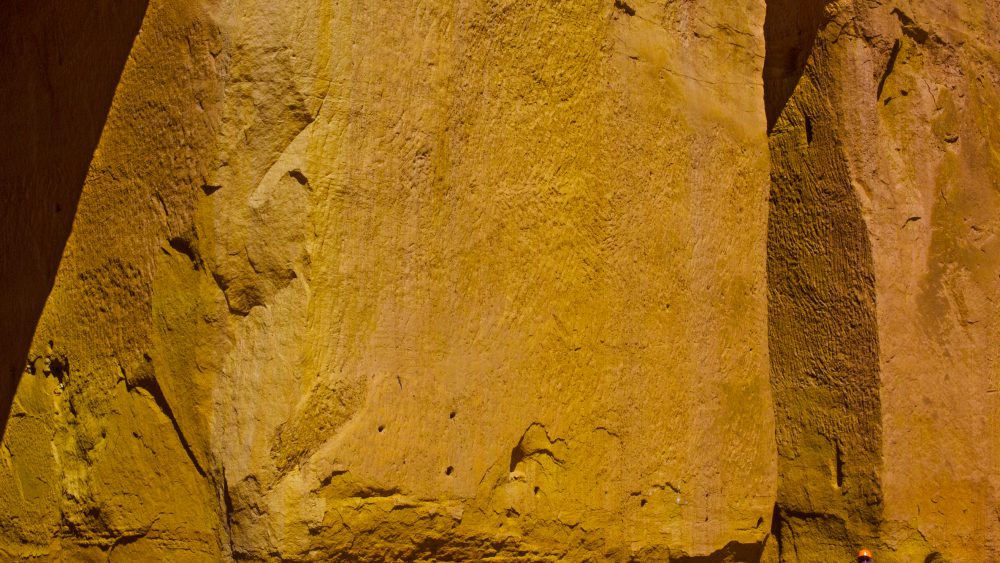

Modern San are the direct descendants of the most spatially stable group in the entire history of Homo sapiens.

MOOWON, in an insightful interview with Dr. James Suzman of Anthropos, explores the concepts of time, technology, affluence, and traditional crafts against the backdrop of modernity—all eye-opening considerations that help one understand the current world of the San,

also known as the "Bushmen".

MOOWON: What compelled you to go to the Kalahari and study the San?

JAMES SUZMAN: I was motivated by a youthful sense of adventure coupled with a desperate desire to escape the bleak winters in Scotland, where I was studying anthropology at university. I was also hopelessly romantic. I liked to imagine that somewhere, out there, far from our world of concrete and diesel, there were still people locked into an organic rhythm of life as hunter-gatherers. Once I got to the Kalahari, of course, I found that the world doesn't always conform to our fantasies.

Now most San live either in resettlement areas or squat on the peripheries of villages, such as Omawewozanyanda, where they improvise homes from what is available.

MOOWON: You have been working with the San for over 20 years. Where have you put your focus?

SUZMAN: I've worked in almost every capacity imaginable, both as an academic and applied researcher. I've been particularly interested in understanding how their lives were transformed by colonialism; how they have coped with the land dispossession and loss; and how they have made sense of the interface between the Stone Age and the digital age. But as an anthropologist, a long-term guest in a community in which you gradually develop strong and enduring interpersonal bonds, you eventually end up getting involved in the issues that matter most to them. The nature of the dramatic changes they have experienced over the last 50 years or so meant that, while I was a novice in their traditional hunting and gathering world, I was well positioned to help them navigate their way through some of the political and economic challenges that now will determine their future—issues like employment rights, political representation, access to medical services or education. As an uninvited guest in someone's community, it is wonderful to discover that you can actually be useful.

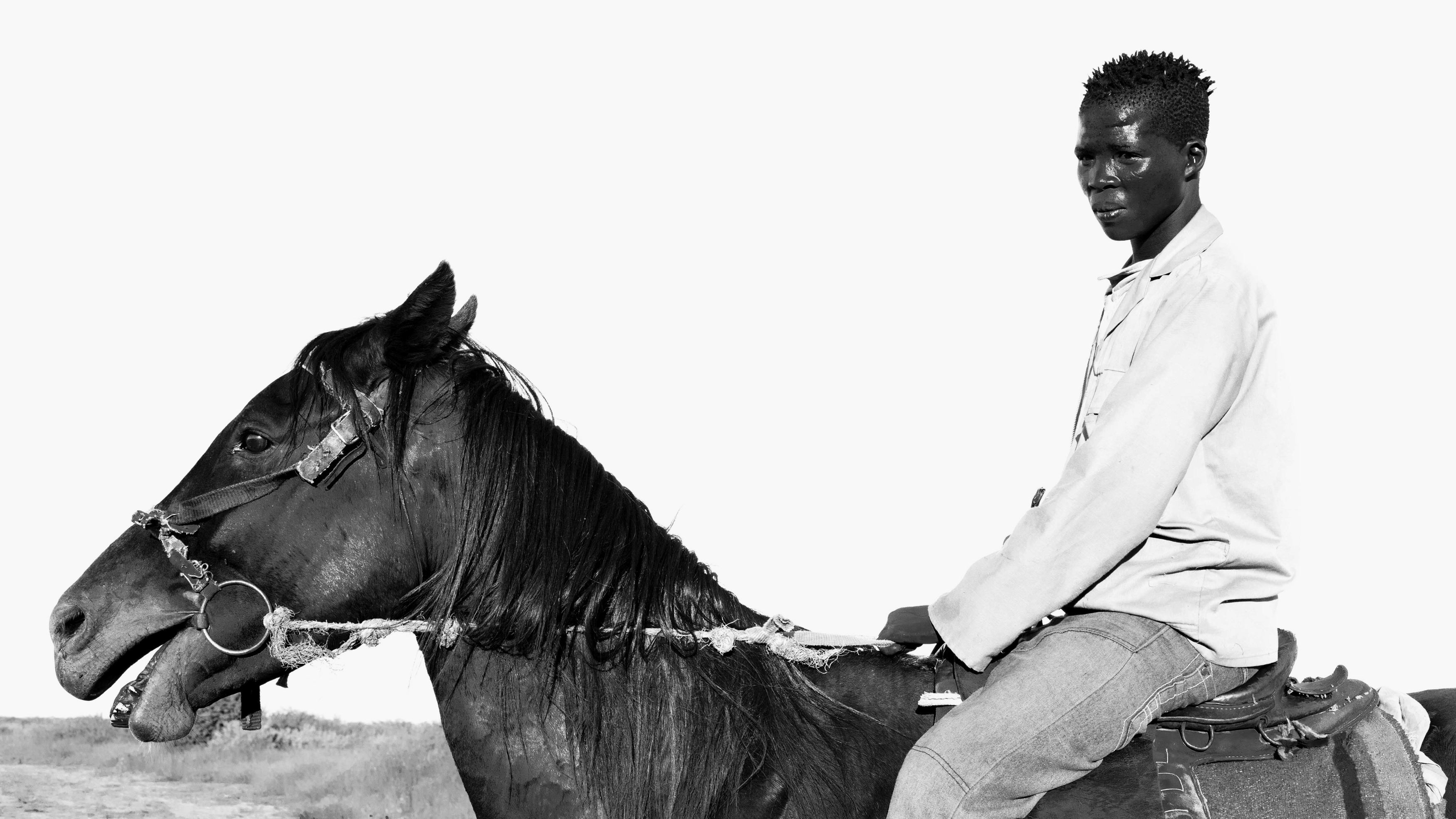

For Modern San like Old Man Jors, who depend on farming rather than hunting, drought is detrimental.

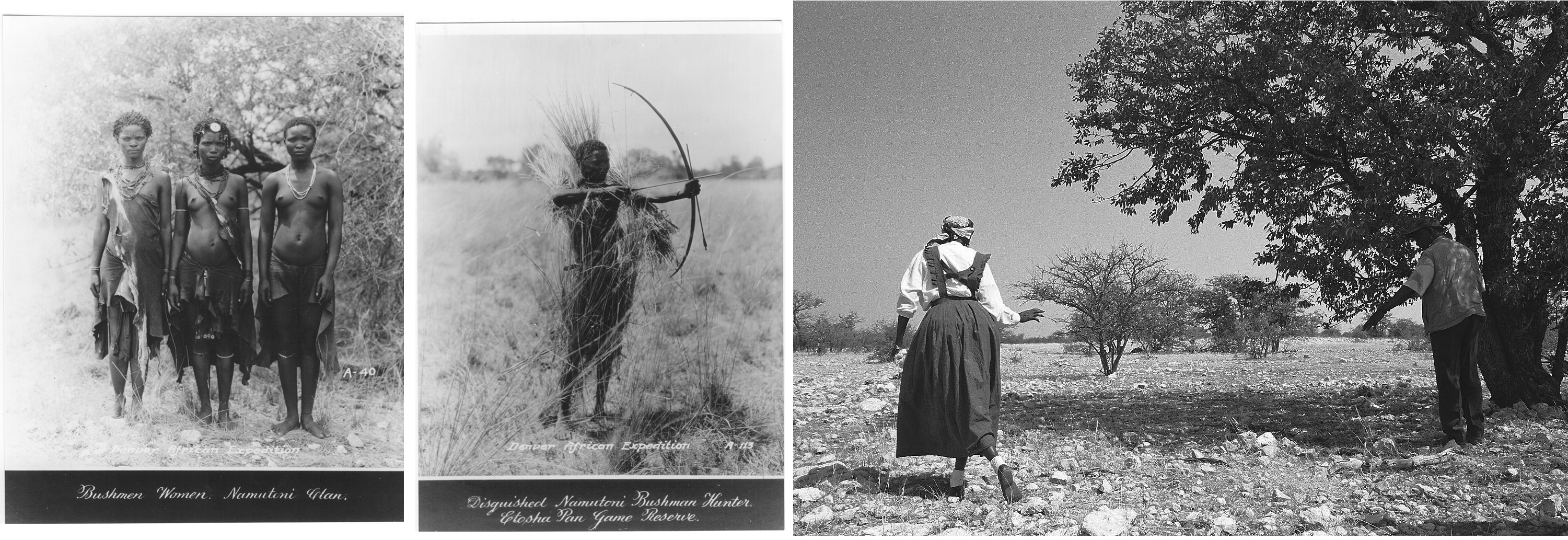

Tikkie explores the site of her old Hai//om village in Etosha National Park from which, in 1954, she and her family were forcibly evicted by nature conservation officials.

Some San, like Willem Douxab (left) still remember how to build their traditional chelters. Others like /Ui Carstens (right) live in resettlement houses they built with the support from the government.

(Left) A shaman traditionally draws on the heat of the fire to reach a state of trance. The Ju/'hoansi San still come together for traditional shamanic healing dances .

(Right) But most San musicians like /I!ae Jors pictured in 1994 now improvise with other instruments to make music. /I!ae committed suicide in 2010 after being released from prison after serving a decade in prison for the murder of his wife.

After the rains, the pans in Nyae-Nyae fill with water and flocks of ducks that play between the elephants.

Please leave your watch

and diary at the

immigration desk.

MOOWON: Tell us about the San's traditional notion of time.

SUZMAN: The idea of time is interesting. We all experience time and imagine it's something that exists objectively outside of us—that it is something real, measurable and objective. So it's very hard to get your head around the idea that different people may experience time very differently. Having said this, I think we are all aware that our experience of time changes from day to day, from hour to hour, or from minute to minute. It sometimes drags interminably. Other times it goes in a flash.

In the urbanized world, I think people are acutely aware of how our sense of time can shape our happiness. People spend lots of money on things like yoga classes, mindfulness counselling, or therapy just so that they can briefly live in the moment. The extraordinary thing about many hunting and gathering cultures is that their practical engagement with their environments created cultures attuned with living in the moment.

When humans changed from hunters and gatherers to farmers, they became hostage to time in a very different way than before. Almost everything a farmer does is future-oriented. Farmers plant seeds and till soil to secure a harvest sometime in the future. When they harvest what they have planted, they hope that it will yield enough to last them through to the next planting season, the next harvest, and so on. This is of course how it is for most of us in the industrialised world. Our work is almost always future-oriented: to fill a pension pot, to pay off a house, to achieve a particular ambition, to learn a particular set of skills for the future.

Economic activities in most hunting and gathering cultures by contrast are focused almost entirely on the here and now. In anthropology, we call these immediate return economies. That means most economic activity is based on satisfying immediate or short-term needs: We are hungry now; therefore, we will go and hunt or gather. This is only possible because hunting and gathering cultures typically have absolute confidence in the providence of their environments and its ability to meet their material needs as and when they arise. And this confidence encourages people to focus very much on the here and now.

San languages reflect this. Most lack the grammatical tools to describe the past or the future, in nuanced and subtle ways, which is of course not the case for languages like English and French. In the San language I know best, Ju/'hoan, the past tense for example is typically denoted by a single participle. Categories to define the past are also limited to broad categories like "earlier", "later", "yesterday", "last month", and "last year". There is no pluperfect, no past imperfect; there are no linear calendars on which to hang memorable events. So the past and the future get compressed into the present.

At the Hai//om resettlement farm Ondera, bathtime is improvised.

!Xoon San waiting for Chief Sofia to address a community meeting at Korridor 17 in eastern Namibia.

When you cease being a hunter-gatherer, which is what has happened for most of the San, there is a massive change in how you engage with time.

MOOWON: How has their notion of time changed with the cash economy?

SUZMAN: When you cease being a hunter-gatherer, which is what has happened for most of the San, there is a massive change in how you engage with time. Over the last 20 to 30 years, the San have had to worry not only about the present but also about their future: "I have to have a job so that I can feed myself", "I have to plan what I am going to do when I am older", "I need to be able to pay for healthcare, school fees", etc. But it's been quite a slow process. Their traditional sense of time was a distinct disadvantage for many San as they tried to cope with the demands of making a living in a cash economy based on labour exchange. Someone who is mainly focused on meeting their immediate needs generally doesn't make a great employee. Employers typically want someone who is focused on working reliably to pay off their house or build up their pension—not someone who works for three hours and then won't come back until the money is spent. San difficulties in adjusting to often draconian labour regimes, imposed by farmers and colonial administrators that took their lands and livelihoods, led to the emergence of numerous crude caricatures of San that described them as "subhuman", childlike or animal-like.

Willem Dauxab, the lion tracker extraordinaire demonstrates the use of a traditional Hai/oom bow and arrow felched with vulture feathers.

Doing shapes our relationship

with the world.

MOOWON: Technology is about having practical solutions to life's needs. How were the San savvy and high-tech as a culture?

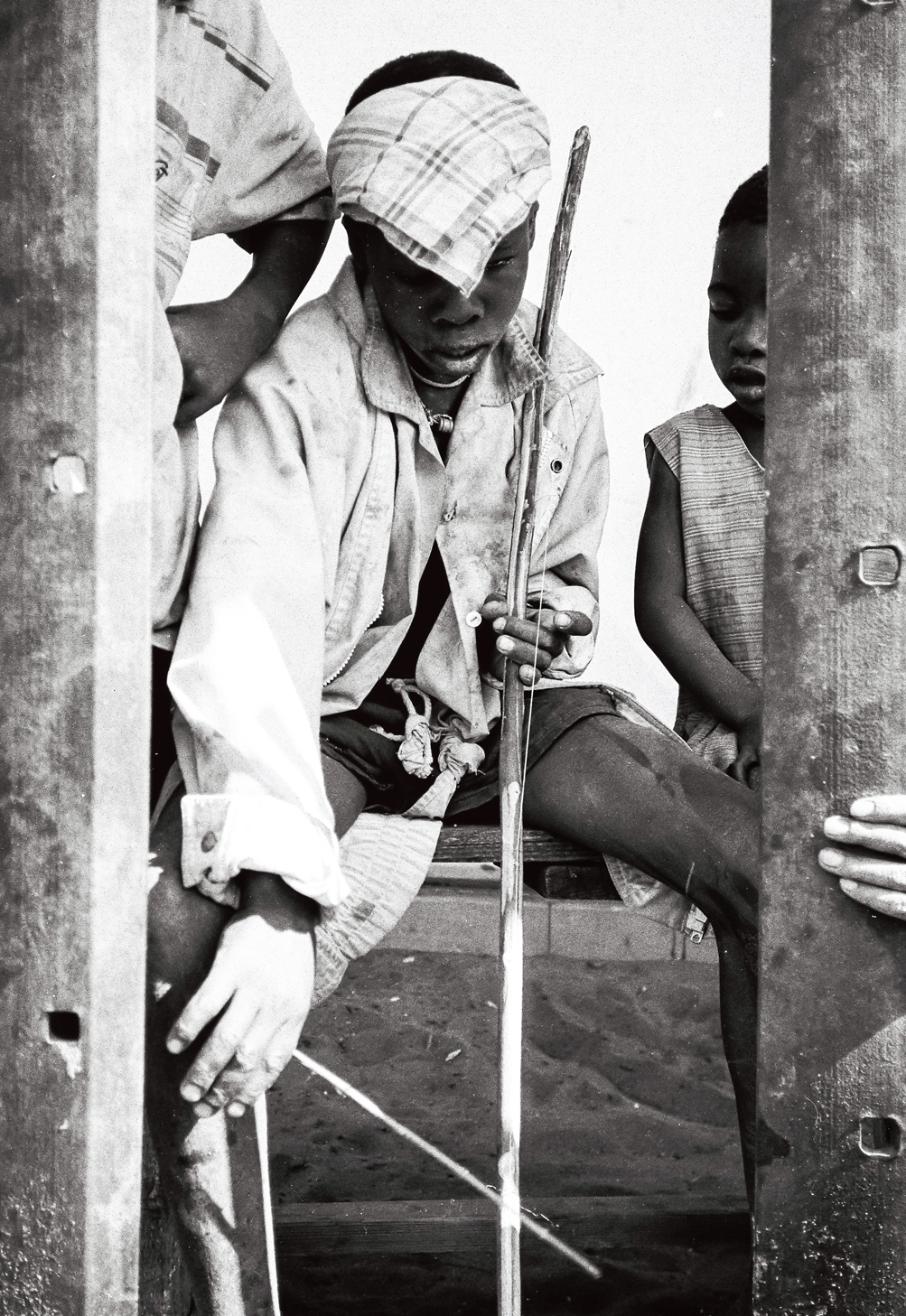

SUZMAN: It seems to me that the more novel technologies we develop, the more needs we create. What was extraordinary with the San was their understanding of how to make a good living with few material desires and on the basis of a handful of simple yet highly refined and appropriate technologies. We, in the industrialised world, have become good at creating technological solutions to problems we encounter, but we are not very good at using this technology to buy ourselves time. The San, by contrast, worked this out long ago. As a society they had achieved a technological level that was able to effectively meet their needs. Their hunting technology for example—the bow and poisoned arrow—was extremely basic yet wonderfully refined and effective.

All their technologies were practical, effective and appropriate. When something worked, it worked. There wasn't a great need in these societies to continuously improve on things; technologies of course would be refined or evolve over time, but there wasn't a drive to endlessly try to improve on things. It wasn't necessary. What they had worked well for them.

MOOWON: What is your thought on the disappearance of technology, and how does this link to the disappearance of culture?

SUZMAN: We often think about culture as being comprised mainly of ideas, languages and objects. But a great deal of culture lies in what we do, in the inarticulate practices or in our embodied memory—how we eat, gesture, hunt or shake hands for example. Culture is also a practical thing. The very practice of hunting is the root of San cosmology and their traditional belief in the fluidity of human and animal identities. I tend to be less stressed about the loss of language than the loss of practice. Doing shapes our relationship with the world. Speaking is only one, admittedly important, form of doing.

A relaxed game of "1-2-3" . A game of mathematical skills where the aim is to steal your opponent's "cattle".

A traditional bow is now often repurposed by children as a string instrument.

That late /'Engn!au Jors, shaman, doctor, storyteller and the last of the "old time people" at Skoonheid Resettlement Camp in Namibia, puffs on his pipe.

The Holboom is a giant baobab tree estimated to be 4500 years old. It lies near the village of Djokxoe in North eastern Namibia, It feeds both the Ju/;'hoansi and elephants that devour it's pods.

We define ourselves

by our aspirations

rather than our present.

MOOWON: For most of us, affluence is often linked to the concept of abundance. Is there another way of thinking about affluence based on what we can learn from the San?

SUZMAN: Affluence is the binding theme here. And it is the focus of a book I am working on that will be published next year or so.

To give you some background: Before the 1960s it was widely believed that hunter-gatherers led a precarious existence—that they endured a constant struggle for survival at the mercy of the elements and wild animals. But it was only in the 1960s that the first detailed research on hunter-gatherer economic life was undertaken. This research focused on the Ju/'hoansi on the Botswana/Namibia border, a group that was still largely dependent on hunting and gathering at the time. And the results of this research blew everyone away. It showed that despite living in an apparently inhospitable desert, the Ju/'hoansi typically worked no more than 15 hours a week to meet their nutritional needs. This contrasts starkly to the industrialised world where we are all expected to work 35 to 40 hours a week. The San, it seemed, had more leisure time than we did. And based on parallel nutritional studies, it also appeared that they were better nourished than many in the industrialised world. For most of year, adult Ju/'hoansi spent only an hour or two per day working and spent the rest of the time with their families…talking, being and relaxing.

Nharo San children improvise a swing out of ripped old clothes and hessian at a farmworkers compound on a safari lodge in eastern Namibia.

Anu demonstrates how seed pods were once used as pipes for tobacco or marijuana.

Preparing maize for grinding it into porridge following good rains.

SUZMAN: So, what is the difference between the hunter-gatherer economic approach and ours? Marshall Sahlins, the author of Stone Age Economics, argued that the San and other societies like them had found a form of "primitive affluence". Here were people who were content not because they had lots of stuff but because they had everything they needed by means of the simple expedient of needing very little. This led Sahlins to reconceptualise affluence not simply as a material condition but rather as a state of mind. Sahlins talked about how hunters and gatherers had mastered the "zen road to affluence". They had found satisfaction through having few needs easily met.

My sense is that the proportional relationship between affluence and abundance in the modern industrial world has become impossible to sustain. We are caught up in an aspiration-fuelled consumption and production loop that has undermined our ability to be satisfied with enough. We continually seek fulfilment in imagining more abundant futures for ourselves. Ironically, many of us work hard just so that we can afford to purchase the next new "labour-saving device".

And doing so also has obvious environmental costs. Many environmental economists argue that if we have not already reached the limits of growth, we soon will. So we now look for technological solutions to the sustainability challenges that face us all. But the endurance of peoples like the San suggest that perhaps a simpler solution is to persuade ourselves to want less stuff—to have fewer, better things.

Old /Kunta showing off his beaded hat donned especially for a BBC film crew in Djokxoe.

There's an opportunity for creative producers

to generate real value and gain recognition.

MOOWON: Amidst these transitions, is the San craft culture being saved from disappearing?

SUZMAN: The San still make crafts for one another to express love, friendship, etc. Wherever you go, you'll come across people who make jewellery or clothing for themselves, as gifts, or as a means of generating a little income. As much as San traditional jewellery is made from things like intricately carved tambotie wood, seeds, or beads fashioned from ostrich eggshells, their artistic tradition is not confined to any particular mediums. San artists and artisans use what is ready to hand. And in the contemporary Kalahari, there are many new things that are ready to hand that can be improvised into jewellery or crafts: fencing wire, tin cans, plastic bags, or car parts.

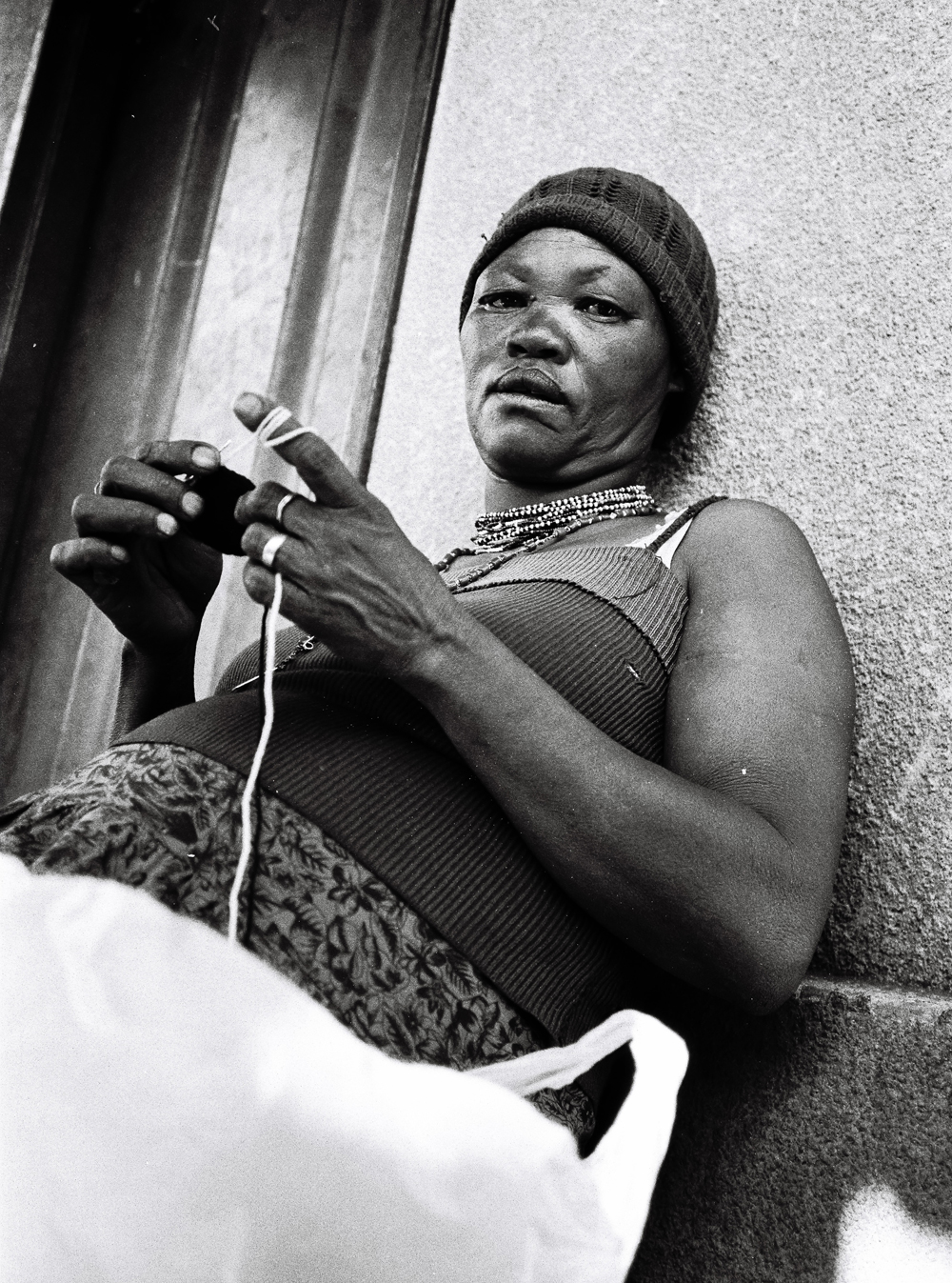

San have proved particularly imaginative when adapting traditional artistic styles to new mediums. One particularly stunning new "tradition" that emerged some decades ago has been the use of historical bead design motifs to make beautiful woollen hats.

Crafts also can play an important role in generating cash for impoverished households. But for these crafts to generate real value and their producers to be recognised for their skill and artistry, a sustainable infrastructure is needed to enable them access to markets. When you're a sole producer, living in a remote village or resettlement area, your ability to access markets is limited. Craft sales tend to be made through tourist ventures or charitable organisations, neither of which is well placed to generate returns commensurate to the artistry and skill of the work.

As a result, San artisans tend to be paid little for their work despite the fact that it is often very labour-intensive, highly-skilled, very creative and draws on an artistic tradition that stretches back several millennia.

Christina //Eng- Skoonhied's most energetic artisan and gardener.

Sofia Kun//a knitting a hat for her nephew at Skoonheid Resettlement Camp.

//Uce tries on her mother's beadwork before it is sold to a white farmer.

Some Hai//om now carve animal sculptures to sell to souvenir hunters at the gates to Etosha National Park in Namibia, their traditional home until their eviction in 1954.

Dr. James Suzman has worked with every major Bushman group in southern Africa, from the war ravaged Vasakele !Kung of southern Angola during the final phases of that civil war, to the highly marginalized Hai//om of Namibia's Etosha National Park. In addition to having published on topics as eclectic as Bushman concepts of time, hunting, spirituality and folklore, Suzman has long been involved in the broader struggle to help secure a sustainable future for southern Africa's Bushmen. In 1998 he was appointed by the European Commission to the largest single research program ever conducted into the human rights status of southern Africa's indigenous peoples. In 2001, Suzman was awarded the Smuts Commonwealth Fellowship in African Studies at Cambridge University. He used the opportunity to return to the Kalahari where he spent five years working with a small group of Hai//om Bushmen elders to map their traditional territories in Etosha National Park. During this time he also advised numerous organizations involved in Bushman matters, including major corporates to the UK Foreign Office and HRH the Prince of Wales. Better known in the Kalahari by his !Kung name, /Kunta, Dr. Suzman remains locked into the Bushman universe. Dr. Suzman is also working on a book about the notion of "primitive affluence" which is due to be published in 2016.

Mona Kim is the Founder and Curator of Moowon magazine. As the Creative Director of award-winning multidisciplinary design studio, Mona Kim Projects, she has been conceiving public space experiences and large-scale experiential projects for global brands and cultural institutions. Her museum and exhibition design for the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, World Expo, Museum of Tomorrow (Museu do Amanhã), and UNESCO-sponsored projects, gave her the opportunity to document and be exposed to some of the most distinctive examples of social realities and cultural expressions. On these projects, she had co-curated world issues such as endangered languages, cultural diversity and sustainability. The Moowon project is an extension of this background. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, WWD(Women's Wear Daily), The Creative Review, and in publications by Gestalten and The Art Institute of Chicago.

EDITING: COPYRIGHT © MOOWON MAGAZINE / MONA KIM PROJECTS LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

PHOTOS: COPYRIGHT © JAMES SUZMAN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

ARCHIVE PHOTOS OF DENVER AFRICAN EXPEDITION : COPYRIGHT © NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF NAMIBIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

INTERVIEW TEXT: COPYRIGHT © MONA KIM / MOOWON MAGAZINE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TO ACQUIRE USAGE RIGHTS, PLEASE CONTACT US at HELLO@MOOWON.COM